Solid and liquid agroindustrial waste materials, from slaughterhouses for example, and wastewater

from sugar/starch processing are not gone into here, since small-scale biogas plants of simple

design would not suffice in that connection (cf. chapter 6).

Waste from animal husbandry

Most simple biogas plants are "fueled" with manure (dung and urine), because such substrates

usually ferment well and produce good biogas yields. Quantity and composition of manure are

primarily dependent on:

- the amount of fodder eaten and its digestibility; on average, 40 - 80% of the organic content

reappears as manure (cattle, for example, excrete approximately 1/3 of their fibrous

fodder),

- quality of fodder utilization and the liveweight of the animals.

It is difficult to offer approximate excrement-yield values, because they are subject to wide variation.

In the case of cattle, for example, the yield can amount to anywhere from 8 to 40 kg per head and

day, depending on the strain in question and the housing intensity. Manure yields should therefore

be either measured or calculated on a liveweight basis, since there is relatively good correlation

between the two methods.

The quantities of manure listed in table 3.2 are only then fully available, if all of the anirnals are kept

in stables all of the time and if the stables are designed for catching urine as well as dung (cf.

chapter 3.3).

Thus, the stated values will be in need of correction in most cases. If cattle are only kept in night

stables, only about 1/3 to 1/2 as much manure can be collected. For cattle stalls with litter, the total

yields will include 2 - 3 kg litter per animal and day.

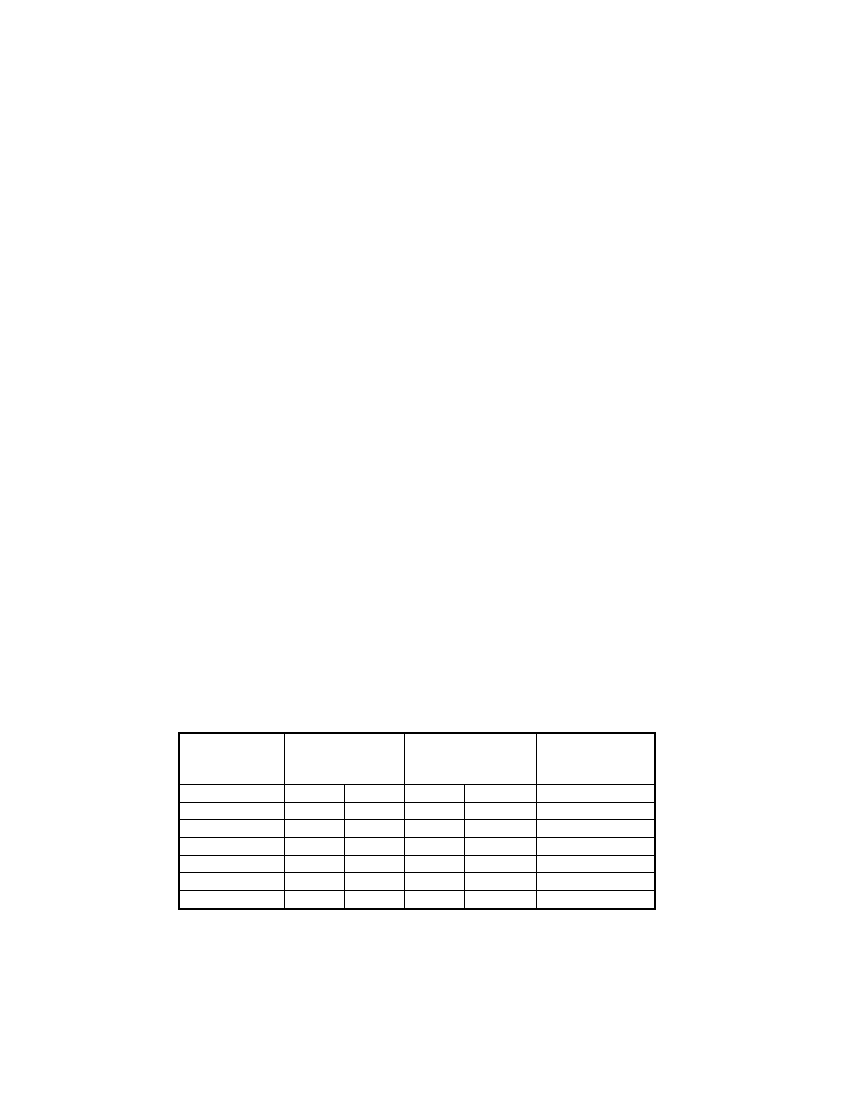

Table 3.2: Standard liveweight values of animal husbandry and average manure yields (dung

and urine) as percentages of liveweight (Source: Kaltwasser 1980, Williamson and Payne

1980)

Species

Cattle

Buffalo

Pigs

Sheep/goats

Chickens

Human

Daily manure

yield as % of

liveweight

dung urine

5 4-5

5 4-5

23

3 1 - 1.5

4.5

12

Fresh-manure

solids

TS (%)

16

14

16

30

25

20

VS (%)

13

12

12

20

17

15

Liveweight

(kg)

135 - 800

340-420

30- 75

30 - 100

1.5 - 2

50- 80

17