Nahuatl

Did you know...

SOS Children made this Wikipedia selection alongside other schools resources. A quick link for child sponsorship is http://www.sponsor-a-child.org.uk/

| Nahuatl | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexicano, Nahuatl, and others | ||||

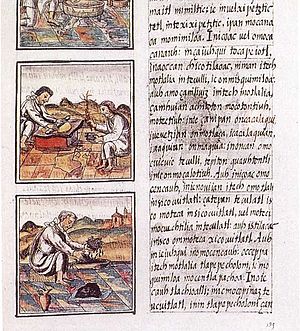

Nahua woman from the Florentine Codex. The speech scroll indicates that she is speaking. |

||||

| Native to | Mexico and El Salvador | |||

| Region | Mexico State, Puebla, Veracruz, Hidalgo, Guerrero, Morelos, Tlaxcala, Oaxaca, Michoacán, Durango, and immigrants in United States, El Salvador, Guatemala and Canada |

|||

| Ethnicity | Nahua peoples | |||

| Native speakers | 1.45 million (2000) | |||

| Language family |

Uto-Aztecan

|

|||

| Early forms: |

Proto-Nahuan

|

|||

| Dialects |

Western Peripheral Nahuatl

Eastern Peripheral Nahuatl

Huastecan Nahuatl

Central Nahuatl

Pipil Nahuat

|

|||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language in | ||||

| Regulated by | Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas | |||

| Language codes | ||||

| ISO 639-2 | nah | |||

| ISO 639-3 | nci Classical Nahuatl For modern varieties, see List of Nahuan languages. |

|||

|

||||

Nahuatl (Nahuatl pronunciation: [ˈnaːwatɬ], with stress on the first syllable) is a language of the Nahuan branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. It is spoken by an estimated 1.5 million Nahua people, most of whom live in Central Mexico; some who live in El Salvador are known as the Pipil people. All Nahuan languages are indigenous to Mesoamerica.

Nahuatl has been spoken in Central Mexico since at least the 7th century AD. It was the language of the Aztecs who dominated what is now central Mexico during the Late Postclassic period of Mesoamerican history. During the centuries preceding the Spanish conquest of Mexico, the Aztec Empire had expanded to incorporate most of Mexico, and its influence caused the variety of Nahuatl spoken by the residents of Tenochtitlan to become a prestige language in Mesoamerica. At the conquest, with the introduction of the Latin alphabet, Nahuatl also became a literary language, and many chronicles, grammars, works of poetry, administrative documents and codices were written in it during the 16th and 17th centuries. This early literary language based on the Tenochtitlan variety has been labeled Classical Nahuatl and is among the most studied and best-documented languages of the Americas.

Today Nahuatl varieties are spoken in scattered communities, mostly in rural areas throughout central Mexico. There are considerable differences among varieties, and some are mutually unintelligible. They have all been subject to varying degrees of influence from Spanish. No modern Nahuatl languages are identical to Classical Nahuatl, but those spoken in and around the Valley of Mexico are generally more closely related to it than those on the periphery. Under Mexico's Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas ("General Law on the Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples") promulgated in 2003, Nahuatl and the other 63 indigenous languages of Mexico are recognized as lenguas nacionales ("national languages") in the regions where they are spoken, enjoying the same status as Spanish within their region.

Nahuatl is a language with a complex morphology characterized by polysynthesis and agglutination ( agglutinative language), allowing the construction of long words with complex meanings out of several stems and affixes. Through centuries of coexistence with the other indigenous Mesoamerican languages, Nahuatl has absorbed many influences, coming to form part of the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area.

Many words from Nahuatl have been borrowed into Spanish, and since diffused into hundreds of other languages. Most of these loanwords denote things indigenous to central Mexico which the Spanish heard mentioned for the first time by their Nahuatl names. English words of Nahuatl origin include "avocado", " chayote", " chili", "chocolate", " atlatl", " coyote", " axolotl" and " tomato".

The place of Nahuatl within Uto-Aztecan

In the past, the branch of Uto-Aztecan to which Nahuatl belongs was called "Aztecan". From the 1990s on, the alternative designation "Nahuan" has been frequently used as a replacement especially in Spanish language publications. The Nahuan (Aztecan) branch of Uto-Aztecan is widely accepted as having two divisions, "General Aztec" and Pochutec.

General Aztec encompasses the Nahuatl and Pipil languages. Pochutec is a scantily attested language which went extinct in the 20th century which Campbell and Langacker classify as being outside of general Aztec. Other researchers argue that Pochutec should be considered a divergent variant of the western periphery.

"Nahuatl" denotes at least Classical Nahuatl together with related modern languages spoken in Mexico. The inclusion of Pipil (Nawat) into the group is slightly controversial. Lyle Campbell classifies Pipil as separate from the Nahuatl branch within general Aztecan, whereas dialectologists like Una Canger, Karen Dakin and Yolanda Lastra prefer to include Pipil in the General Aztecan branch, citing close historical ties with the eastern peripheral dialects of General Aztec.

History

Pre-Columbian period

On the issue of geographic origin, linguists during the 20th century agreed that the Uto-Aztecan language family originated in the southwestern United States. Recent studies have tried to uncover the history of the Nahuatl language by advocating a migration of Asian populations across the Bering strait. Studies that have found word pairings between Nahuatl and Altaic Ural-Turkic (i.e. mountain, Nahuatl: Tepec, Turkish: Tepe.) Apart from these recent studies, evidence from archaeology and ethnohistory supports a southward diffusion across the American continent thesis, specifically that speakers of early Nahuan languages migrated from the northern Mexican deserts into central Mexico in several waves. But recently, the traditional assessment has been challenged by Jane H. Hill, who proposes instead that the Uto-Aztecan language family originated in central Mexico and spread northwards at a very early date. This hypothesis and the analyses of data that it rests upon have received serious criticism.

The purported migration of speakers of the Proto-Nahuan language into the Mesoamerican region has been placed at sometime around AD 500, towards the end of the Early Classic period in Mesoamerican chronology. Before reaching the central altiplano, pre-Nahuan groups probably spent a period of time in contact with the Coracholan languages Cora and Huichol of northwestern Mexico (which are also Uto-Aztecan).

The major political and cultural centre of Mesoamerica in the Early Classic period was Teotihuacan. The identity of the language(s) spoken by Teotihuacan's founders has long been debated, with the relationship of Nahuatl to Teotihuacan being prominent in that enquiry. While in the 19th and early 20th centuries it was presumed that Teotihuacan had been founded by speakers of Nahuatl, later linguistic and archaeological research tended to disconfirm this view. Instead, the timing of the Nahuatl influx was seen to coincide more closely with Teotihuacan's fall than its rise, and other candidates such as Totonacan identified as more likely. But recently, evidence from Mayan epigraphy of possible Nahuatl loanwords in Mayan languages has been interpreted as demonstrating that other Mesoamerican languages may have been borrowing words from Proto-Nahuan (or its early descendants) significantly earlier than previously thought, bolstering the possibility of a significant Nahuatl presence at Teotihuacan.

In Mesoamerica the Mayan, Oto-Manguean and Mixe–Zoquean language families had coexisted for millennia. This had given rise to the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area (a linguistic area being one where a set of language traits have become common among the area's languages by diffusion and not by evolution within a set of languages belonging to a common genetic subgrouping). After the Nahuas migrated into the Mesoamerican cultural zone, their language too adopted some of the traits defining the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area. Examples of such adopted traits are the use of relational nouns, the appearance of calques, or loan translations, and a form of possessive construction typical of Mesoamerican languages.

A language which was the ancestor of Pochutec split from Proto-Nahuan (or Proto-Aztecan) possibly as early as AD 400, arriving in Mesoamerica a few centuries earlier than the main bulk of speakers of Nahuan languages. Some Nahuan groups migrated south along the Central American isthmus, reaching perhaps as far as Nicaragua. The moribund Pipil language of El Salvador is the only living descendant of the variety of Nahuatl once spoken south of present day Mexico.

Beginning in the 7th century Nahuan speakers rose to power in central Mexico. The people of the Toltec culture of Tula, which was active in central Mexico around the 10th century, are thought to have been Nahuatl speakers. By the 11th century, Nahuatl speakers were dominant in the Valley of Mexico and far beyond, with settlements including Azcapotzalco, Colhuacan and Cholula rising to prominence. Nahua migrations into the region from the north continued into the Postclassic period. One of the last of these migrations to arrive in the Valley of Mexico settled on an island in the Lake Texcoco and proceeded to subjugate the surrounding tribes. This group was the Mexica (or Mexihka), who over the course of the next three centuries founded an empire named Tenochtitlan. Their political and linguistic influence came to extend into Central America and Nahuatl became a lingua franca among merchants and elites in Mesoamerica, e.g., among the Quiché (K'iche') Maya. As Tenochtitlan grew to become the largest urban centre in Central America, it attracted speakers of Nahuatl from diverse areas giving birth to an urban form of Nahuatl with traits from many dialects. This urbanized variety of Tenochtitlan is what came to be known as Classical Nahuatl documented in colonial times.

Colonial period

With the arrival of the Spanish in 1519, the tables were turned on the Nahuatl language: it was displaced as the dominant regional language. Nevertheless, due to the Spanish making alliances with first the Nahuatl speakers from Tlaxcala and later with the conquered Aztecs, the Nahuatl language continued spreading throughout Mesoamerica in the decades after the conquest, when Spanish expeditions with thousands of Nahua soldiers marched north and south to conquer new territories. Jesuit missions in northern Mexico and the southwestern US region often included a barrio of Tlaxcaltec soldiers who remained to guard the mission. For example, some fourteen years after the northeastern city of Saltillo, Coahuila, was founded in 1577, a Tlaxcaltec community was resettled in a separate nearby village, San Esteban de Nueva Tlaxcala to cultivate the land and aid colonization efforts that had stalled in the face of local hostility to the Spanish settlement. As for the conquest of modern day Central America, Pedro de Alvarado conquered Guatemala with the help of tens of thousands of Tlaxcaltec allies, who then settled outside of modern day Antigua. Similar episodes occurred across El Salvador and Honduras, with Nahuatl speakers settling in communities that were often named after them. In Honduras for example, two of these barrios are called "Mexicapa"; another in El Salvador is called "Mejicanos".

As a part of their missionary efforts, members of various religious orders (principally Fransciscan friars, Dominican friars, and Jesuits) introduced the Latin alphabet to the Nahuas. Within the first twenty years after the Spanish arrival, texts were being prepared in the Nahuatl language written in Latin characters. Simultaneously, schools were founded, such as the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in 1536, which taught both indigenous and classical European languages to both Indians and priests. Missionary grammarians undertook the writing of grammars of indigenous languages for use by priests. The first Nahuatl grammar, written by Andrés de Olmos, was published in 1547—three years before the first French grammar. By 1645 four more had been published, authored respectively by Alonso de Molina (1571), Antonio del Rincón (1595), Diego de Galdo Guzmán (1642), and Horacio Carochi (1645). Carochi's is today considered the most important of the colonial era grammars of Nahuatl.

In 1570 King Philip II of Spain decreed that Nahuatl should become the official language of the colonies of New Spain in order to facilitate communication between the Spanish and natives of the colonies. This led to the Spanish missionaries teaching Nahuatl to Indians living as far south as Honduras and El Salvador. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Classical Nahuatl was used as a literary language, and a large corpus of texts from that period is in existence today. Texts from this period include histories, chronicles, poetry, theatrical works, Christian canonical works, ethnographic descriptions, and administrative documents. The Spanish permitted a great deal of autonomy in the local administration of indigenous towns during this period, and in many Nahuatl speaking towns Nahuatl was the de facto administrative language both in writing and speech. A large body of Nahuatl literature was composed during this period, including the Florentine Codex, a twelve-volume compendium of Aztec culture compiled by Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún; Crónica Mexicayotl, a chronicle of the royal lineage of Tenochtitlan by Fernando Alvarado Tezozómoc; Cantares Mexicanos, a collection of songs in Nahuatl; a Nahuatl-Spanish/Spanish-Nahuatl dictionary compiled by Alonso de Molina; and the Huei tlamahuiçoltica, a description in Nahuatl of the apparition of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Grammars and dictionaries of indigenous languages were composed throughout the colonial period, but their quality was highest in the initial period. The friars found that learning all the indigenous languages was impossible in practice, so they concentrated on Nahuatl. For a time, the linguistic situation in Mesoamerica remained relatively stable, but in 1696 King Charles II issued a decree banning the use of any language other than Spanish throughout the Spanish Empire. In 1770 another decree, calling for the elimination of the indigenous languages, did away with Classical Nahuatl as a literary language.

Modern period

| Region | Totals | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Federal District | 37,450 | 0.44% |

| Guerrero | 136,681 | 4.44% |

| Hidalgo | 221,684 | 9.92% |

| Mexico (state) | 55,802 | 0.43% |

| Morelos | 18,656 | 1.20% |

| Oaxaca | 10,979 | 0.32% |

| Puebla | 416,968 | 8.21% |

| San Luis Potosí | 138,523 | 6.02% |

| Tlaxcala | 23,737 | 2.47% |

| Veracruz | 338,324 | 4.90% |

| Rest of Mexico | 50,132 | 0.10% |

| Total: | 1,448,937 | 1.49% |

Throughout the modern period the situation of indigenous languages has grown increasingly precarious in Mexico, and the numbers of speakers of virtually all indigenous languages have dwindled. Although the absolute number of Nahuatl speakers has actually risen over the past century, indigenous populations have become increasingly marginalized in Mexican society. In 1895, Nahuatl was spoken by over 5% of the population. By 2000, this proportion had fallen to 1.49%. Given the process of marginalization combined with the trend of migration to urban areas and to the United States, some linguists are warning of impending language death. At present Nahuatl is mostly spoken in rural areas by an impoverished class of indigenous subsistence agriculturists. According to the Mexican national statistics institute, INEGI, 51% of Nahuatl speakers are involved in the farming sector and 6 in 10 receive no wages or less than the minimum wage.

From the early 20th century to at least the mid-1980s, educational policies in Mexico focused on the hispanization (castellanización) of indigenous communities, teaching only Spanish and discouraging the use of indigenous languages. As a result, today there is no group of Nahuatl speakers having attained general literacy in Nahuatl; while their literacy rate in Spanish also remains much lower than the national average. Even so, Nahuatl is still spoken by well over a million people, of whom around 10% are monolingual. The survival of Nahuatl as a whole is not imminently endangered, but the survival of certain dialects is, and some dialects have already become extinct within the last few decades of the 20th century.

The 1990s saw the onset of diametric changes in official Mexican government policies towards indigenous and linguistic rights. Developments of accords in the international rights arena combined with domestic pressures led to legislative reforms and the creation of decentralized government agencies like CDI and INALI with responsibilities for the promotion and protection of indigenous communities and languages. In particular, the federal Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas ["General Law on the Language Rights of the Indigenous Peoples", promulgated 13 March 2003] recognizes all the country's indigenous languages, including Nahuatl, as " national languages" and gives indigenous people the right to use them in all spheres of public and private life. In Article 11, it grants access to compulsory, bilingual and intercultural education.

In February 2008 the mayor of Mexico City, Marcelo Ebrard, launched a drive to have all government employees learn Nahuatl. Ebrard stated he would continue institutionalizing Nahuatl and that it was important for Mexico to remember its history and its tradition.

Geographic distribution

Today, a spectrum of Nahuatl dialects are spoken in an scattered areas stretching from the northern state of Durango to Veracruz in the southeast. Pipil (also known as Nawat), the southernmost Nahuan language, is spoken in El Salvador by a small number of speakers. According to IRIN-International, the Nawat Language Recovery Initiative project, there are no reliable figures for the contemporary numbers of speakers of Pipil / Nawat. Numbers may range anywhere from "perhaps a few hundred people, perhaps only a few dozen."

According to the 2000 census of the Mexican statistical Institute INEGI, Nahuatl is spoken by an estimated 1.45 million people, some 198,000 (14.9%) of whom are monolingual. There are many more female than male monolinguals, females represent nearly two thirds of the total number. The states of Guerrero and Hidalgo have the highest rates of monolingual Nahuatl speakers relative to the total Nahuatl speaking population. Guerrero has 24.2% and Hidalgo 22.6%, monolinguals. For most other states the percentage of monolinguals among the speakers is less than 5%. This means that in most states more than 95% of the Nahuatl speaking population are bilingual in Spanish. These statistics do not consider the possibility of monolingual speakers of Nahuatl also speaking additional indigenous languages.

The largest concentrations of Nahuatl speakers are found in the states of Puebla, Veracruz, Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí, and Guerrero. Significant populations are also found in Mexico State, Morelos, and the Federal District, with smaller communities in Michoacán and Durango. Nahuatl became extinct during the 20th century in the states of Jalisco and Colima. As a result of internal migrations within the country, Nahuatl speaking communities exist in all of Mexico's states. The modern influx of Mexican workers and families into the United States has resulted in the establishment of a few small Nahuatl speaking communities in that country, particularly in California, New York, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

Subclassification of Nahuatl dialects

Terminology

The terminology used to describe varieties of spoken Nahuatl is inconsistently applied. Many terms are used with multiple denotations, or a single dialect grouping goes under several names. Sometimes older terms are substituted with newer ones or with the speakers' own name for their specific variety. The word Nahuatl is itself a Nahuatl word, probably derived from the word nāwatlaʔtōlli ("clear language"). The language was formerly called "Aztec" because it was spoken by the Aztecs, who however didn't call themselves Aztecs but mexícâ, and their language mexícacopa. Nowadays the term "Aztec" is rarely used for modern Nahuan languages, but linguists' traditional name of "Aztecan" for the branch of Uto-Aztecan that comprises Nahuatl, Pipil, and Pochutec is still in use (although some linguists prefer "Nahuan"). Since 1978, the term "General Aztec" has been adopted by linguists to refer to the languages of the Aztecan branch excluding Pochutec.

The speakers of Nahuatl themselves often refer to their language as either Mexicano or some word derived from mācēhualli, the Nahuatl word for "commoner". One example of the latter is the case for Nahuatl spoken in Tetelcingo, Morelos, whose speakers call their language mösiehuali. The Pipil of El Salvador do not call their own language "Pipil", as most linguists do, but rather nawat. The Nahuas of Durango call their language Mexicanero. Speakers of Nahuatl of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec call their language mela'tajtol ("the straight language"). Some speech communities use "Nahuatl" as the name for their language although this seems to be a recent innovation. Linguists commonly identify localized dialects of Nahuatl by adding as a qualifier the name of the village or area where that variety is spoken.

Dialectology

Current subclassification of Nahuatl rests on research by Canger (1980, 1988) and Lastra de Suárez (1986). Canger introduced the scheme of a Central grouping several Peripheral groupings, and Lastra confirmed this notion, differing in some details. Each of the groupings is defined by shared characteristic grammatical features which in turn suggest a shared history. Canger includes dialects of La Huasteca in the Centre Peripheral group, while Lastra de Suárez places them in their own subgroup of Peripheral. Below, Lastra de Suarez's classification is combined with Campbell 1997's classification of Uto-Aztecan. (Campbell's positing of higher level subgroupings of Uto-Aztecan, specifically "Shoshonean" and "Sonoran", above the eight uncontroversial branches is not yet generally accepted. Also, Lastra's including Pipil under Nahuatl is not accepted by Campbell, who has been the leading investigator of Pipil.)

- Uto-Aztecan 5000 BP*

- Aztecan 2000 BP (AKA Nahuan)

- Pochutec † Coast of Oaxaca

- General Aztec (including Nahuatl)

- Western Periphery Dialects of Durango (Mexicanero), Michoacán, Western Mexico state, extinct dialects of Colima and Nayarit

- Eastern Periphery Pipil language and dialects of Sierra de Puebla, southern Veracruz and Tabasco (Isthmus dialects)

- Huasteca Dialects of northern Puebla, Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí and northern Veracruz

- Centre Dialects of central Puebla, Tlaxcala, central Veracruz, Morelos, Mexico state, central and southern Guerrero

- Aztecan 2000 BP (AKA Nahuan)

- *Estimated split date by glottochronology (BP = years Before Present).

Phonology

Nahuan languages are defined as a subgroup of Uto-Aztecan by having undergone a number of shared changes from the Uto-Aztecan protolanguage (PUA). The table below shows the phonemic inventory of Classical Nahuatl as an example of a typical Nahuan language. In some dialects the /t͡ɬ/ phoneme that is so common in classical Nahuatl has changed into either /t/ as it has happened in Isthmus-Mecayapan Nahuatl, Mexicanero and Pipil or into /l/ as it has happened in Nahuatl of Pómaro, Michoacán. Many dialects no longer distinguish between short and long vowels. Some have introduced completely new vowel qualities to compensate for this, as is the case for Tetelcingo Nahuatl. Others have developed a pitch accent, such as Nahuatl of Oapan, Guerrero. Many modern dialects have also borrowed phonemes from Spanish, such as /b, d, ɡ, f/.

Sounds

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- * The glottal phoneme (called the " saltillo") only occurs after vowels. In many modern dialects it is realized as an [h], but in classical Nahuatl and in other modern dialects it is a glottal stop [ʔ].

Most Nahuatl dialects have stress on the penultimate syllable of a word. In Mexicanero Nahuat from Durango, many unstressed syllables have disappeared from words, and the placement of syllable stress has become phonemic in this dialect

Allophony

Most varieties have relatively simple patterns of sound alternation (allophony). In many dialects the voiced consonants are devoiced in wordfinal position and in consonant clusters: /j/ devoices to a voiceless palatal sibilant /ʃ/, /w/ devoices to a voiceless glottal fricative [h] or to a voiceless labialized velar approximant [ʍ], and /l/ devoices to voiceless alveolar lateral fricative [ɬ]. In some dialects the first consonant in almost any consonant cluster becomes [h]. Some dialects have productive lenition of voiceless consonants into their voiced counterparts between vowels. The nasals are normally assimilated to the place of articulation of a following consonant. The voiceless alveolar lateral affricate [t͡ɬ] is assimilated after /l/ and pronounced [l].

Phonotactics

Classical Nahuatl and most of the modern varieties have fairly simple phonological systems. They allow only syllables with maximally one initial and one final consonant. Consonant clusters only occur wordmedially and over syllable boundaries. Some morphemes have two alternating forms, one with a vowel i to prevent consonant clusters, and one without. For example, the absolutive suffix has the variant forms – tli (used after consonants) and – tl (used after vowels). Some modern varieties however have formed complex clusters due to vowel loss. Others have contracted syllable sequences, causing accents to shift or vowels to become long.

Reduplication

Many varieties of Nahuatl have productive reduplication. By reduplicating the first syllable of a root a new word is formed. In nouns this is often used to form plurals, e.g. /tlaːkatl/ "man" > /tlaːtlaːkah/ "men", but also in some varieties to form diminutives, honorifics, or for derivations. In verbs reduplication is often used to form a reiterative (expressing repetition), e.g. /kitta/ "he sees it", /kihitta/ "he looks at it repeatedly".

Grammar

The Nahuatl languages are agglutinative, polysynthetic languages that make extensive use of compounding, incorporation and derivation. That is, they can add many different prefixes and suffixes to a root until very long words are formed – and a single word can constitute an entire sentence.

The following verb shows how the verb is marked for subject, patient, object, and indirect object:

-

- /ni-mits-teː-tla-makiː-ltiː-s/

- I-you-someone-something-give-CAUSATIVE-FUTURE

- "I shall make somebody give something to you" (Classical Nahuatl)

Nouns

The Nahuatl noun has a relatively complex structure. The only obligatory inflections are for number (singular and plural) and possession (i.e., whether the noun is possessed, as is indicated by a prefix meaning 'my', 'your', etc.). Nahuatl has neither case nor gender, but Classical Nahuatl and some modern dialects distinguish between animate and inanimate nouns. In Classical Nahuatl the animacy distinction manifested with respect to pluralization, as only animate nouns could take a plural form, whereas all inanimate nouns were uncountable (as the words "bread" and "money" are uncountable in English). Nowadays many dialects do not maintain this distinction and all nouns may take the plural inflection.

In most varieties of Nahuatl, nouns in the unpossessed singular form generally take an "absolutive" suffix. The most common forms of the absolutive are -tl after vowels, -tli after consonants other than l, and -li after l. Nouns that take the plural usually form the plural by adding one of the plural absolutive suffixes -tin or -meh, although some plural forms are irregular, or formed by reduplication. Some nouns have competing plural forms.

|

Singular noun:

|

Plural animate noun:

|

Plural animate noun w. reduplication:

- /ko:-kojo-h/

- REDUPLcoyote-PLURAL

- "coyotes" (Classical Nahuatl)

Nahuatl distinguishes between possessed and unpossessed forms of nouns. The absolutive suffix is not used on possessed nouns. In all dialects, possessed nouns take a prefix agreeing with number and person of its possessor. Possessed plural nouns take the ending -wa:n.

|

Absolutive noun:

|

Possessed noun:

|

Possessed plural:

- /no-kal-wa:n/

- my-house-PLURAL

- "my houses" (Classical Nahuatl)

Nahuatl does not have grammatical case but uses what is sometimes called a relational noun to describe spatial (and other) relations. These morphemes cannot appear alone but must always occur after a noun or a possessive prefix. They are also often called postpositions or locative suffixes. In some ways these locative constructions resemble, and can be thought of as, locative case constructions. Most modern dialects have incorporated prepositions from Spanish that are competing with or that have completely replaced relational nouns.

|

Uses of relational noun/postposition/locative -pan with a possessive prefix:

|

Use with a preceding noun stem:

|

Noun compounds are commonly formed by combining two or more nominal stems, or combining a nominal stem with an adjectival or verbal stem.

Pronouns

Nahuatl generally distinguishes three persons – both in the singular and plural numbers. In at least one modern dialect, the Isthmus-Mecayapan variety, there has come to be a distinction between inclusive (I/we and you) and exclusive (we but not you) forms of the first person plural:

|

First person plural pronoun in Classical Nahuatl:

|

First person plural pronouns in Isthmus-Mecayapan Nahuat:

|

Much more common is an honorific/non-honorific distinction, usually applied to second and third persons but not first.

|

Non-honorific forms:

|

Honorific forms

|

Verbs

The Nahuatl verb is quite complex and inflects for many grammatical categories. The verb is composed of a root, prefixes, and suffixes. The prefixes indicate the person of the subject, and person and number of the object and indirect object, whereas the suffixes indicate tense, aspect, mood and subject number.

Most Nahuatl dialects distinguish three tenses: present, past, and future, and two aspects: perfective and imperfective. Some varieties add progressive or habitual aspects. All dialects distinguish at least the indicative and imperative moods, while some also have optative and vetative moods.

Most Nahuatl varieties have a number of ways to alter the valency of a verb. Classical Nahuatl had a passive voice (also sometimes defined as an impersonal voice), but this is not found in most modern varieties. However the applicative and causative voices are found in many modern dialects. Many Nahuatl varieties also allow forming verbal compounds with two or more verbal roots.

The following verbal form has two verbal roots and is inflected for causative voice and both a direct and indirect object:

- ni-kin-tla-kwa-ltiː-s-neki

- I-them-something-eat-CAUSATIVE-FUTURE-want

- "I want to feed them" (Classical Nahuatl)

Some Nahuatl varieties, notably Classical Nahuatl, can inflect the verb to show the direction of the verbal action going away from or towards the speaker. Some also have specific inflectional categories showing purpose and direction and such complex notions as "to go in order to" or "to come in order to", "go, do and return", "do while going", "do while coming", "do upon arrival", or "go around doing".

Classical Nahuatl and many modern dialects have grammaticalised ways to express politeness towards addressees or even towards people or things that are being mentioned, by using special verb forms and special "honorific suffixes".

|

Familiar verbal form:

|

Honorific verbal form:

|

Syntax

Some linguists have argued that Nahuatl displays the properties of a non-configurational language, meaning that word order in Nahuatl is basically free. Nahuatl allows all possible orderings of the three basic sentence constituents. It is prolifically a pro-drop language: it allows sentences with omission of all noun phrases or independent pronouns, not just of noun phrases or pronouns whose function is the sentence subject. In most varieties independent pronouns are used only for emphasis. It allows certain kinds of syntactically discontinuous expressions.

Michel Launey argues that Classical Nahuatl had a verb-initial basic word order with extensive freedom for variation, which was then used to encode pragmatic functions such as focus and topicality. The same has been argued for some contemporary varieties.

- newal no-nobia

- I my-fianceé

- "My fiancée "(and not anyone else's) (Michoacán Nahual)

It has been argued that classical Nahuatl syntax is best characterised by "omnipredicativity", meaning that any noun or verb in the language is in fact a full predicative sentence. A radical interpretation of Nahuatl syntactic typology, this nonetheless seems to account for some of the language's peculiarities, for example, why nouns must also carry the same agreement prefixes as verbs, and why predicates do not require any noun phrases to function as their arguments. For example the verbal form tzahtzi means "he/she/it shouts", and with the second person prefix titzahtzi it means "you shout". Nouns are inflected in the same way: the noun "conētl" means not just "child", but also "it is a child", and ticonētl means "you are a child". This prompts the omnipredicative interpretation, which posits that all nouns are also predicates. According to this interpretation a phrase such as tzahtzi in conētl should not be interpreted as meaning just "the child screams" but, more rather, "it screams, (the one that) is a child".

Contact phenomena

Nearly 500 years of intense contact between speakers of Nahuatl and speakers of Spanish, combined with the minority status of Nahuatl and the higher prestige associated with Spanish has caused many changes in modern Nahuatl varieties, with large numbers of words borrowed from Spanish into Nahuatl, and the introduction of new syntactic constructions and grammatical categories.

For example, a construction like the following, with several borrowed words and particles, is common in many modern varieties (Spanish loanwords in boldface):

- pero āmo tēchentenderoah lo que tlen tictoah en mexicano

- but not they-us-understand-PLURAL that which what we-it-say in Nahuatl

- "But they don't understand what we say in Nahuatl" (Malinche Nahuatl)

In some modern dialects basic word order has become a fixed subject–verb–object, probably under influence from Spanish. Other changes in the syntax of modern Nahuatl include the use of Spanish prepositions instead of native postpositions or relational nouns and the reinterpretation of original postpositions/relational nouns into prepositions. In the following example, from Michoacán Nahual, the postposition -ka meaning "with" appears used as a preposition, with no preceding object:

- ti-ya ti-k-wika ka tel

- you-go you-it-carry with you

- "are you going to carry it with you?" (Michoacán Nahual)

And, in this example from Mexicanero Nahuat, of Durango, the original postposition/relational noun -pin "in/on" is used as a preposition. "porque", a preposition borrowed from Spanish, also occurs in the sentence.

- amo wel kalaki-yá pin kal porke ȼakwa-tiká im pwerta

- not can he-enter-PAST in house because it-closed-was the door

- "He couldn't enter the house because the door was closed" (Mexicanero Nahuat)

Many dialects have also undergone a degree of simplification of their morphology which has caused some scholars to consider them to have ceased to be polysynthetic.

Vocabulary

Many Nahuatl words have been borrowed into the Spanish language, most of which are terms designating things indigenous to the American continent. Some of these loans are restricted to Mexican or Central American Spanish, but others have entered all the varieties of Spanish in the world. A number of them, such as "chocolate", "tomato" and "avocado" have made their way into many other languages via Spanish.

Likewise a number of English words have been borrowed from Nahuatl through Spanish. Two of the most prominent are undoubtedly chocolate and tomato (from Nahuatl tomatl). Other common words such as coyote (from Nahuatl coyotl), avocado (from Nahuatl ahuacatl) and chile or chili (from Nahuatl chilli). The word chicle is also derived from Nahuatl tzictli "sticky stuff, chicle". Some other English words from Nahuatl are: Aztec, (from aztecatl); cacao (from Nahuatl cacahuatl 'shell, rind'); ocelot (from ocelotl). In Mexico many words for common everyday concepts attest to the close contact between Spanish and Nahuatl, so many in fact that entire dictionaries of "mexicanismos" (words particular to Mexican Spanish) have been published tracing Nahuatl etymologies, as well as Spanish words with origins in other indigenous languages. Many well known toponyms also come from Nahuatl, including Mexico (from the Nahuatl word for the Aztec capital mexihco) and Guatemala (from the word cuauhtēmallan).

Writing and literature

Writing

Pre-Columbian Aztec writing was not a true writing system, since it could not represent the full vocabulary of a spoken language in the way that the writing systems of the Old World or the Maya Script could. Therefore, Aztec writing was not meant to be read, but to be told. The elaborate codices were essentially pictographic aids for memorizing texts, which include genealogies, astronomical information, and tribute lists. Three kinds of signs were used in the system: pictures used as mnemonics (which do not represent particular words), logograms which represent whole words (instead of phonemes or syllables), and logograms used only for their sound values (i.e. used according to the rebus principle).

The Spanish introduced the Latin script, which was used to record a large body of Aztec prose, poetry and mundane documentation such as testaments, administrative documents, legal letters, etc. In a matter of decades pictorial writing was completely replaced with the Latin alphabet. No standardized Latin orthography has been developed for Nahuatl, and no general consensus has arisen for the representation of many sounds in Nahuatl that are lacking in Spanish, such as long vowels and the glottal stop. The orthography most accurately representing the phonemes of Nahuatl was developed in the 17th century by the Jesuit Horacio Carochi. Carochi's orthography used two different accents: a macron to represent long vowels and a grave for the saltillo, and sometimes an acute accent for short vowels. This orthography did not achieve a wide following outside of the Jesuit community.

When Nahuatl became the subject of focused linguistic studies in the 20th century, linguists acknowledged the need to represent all the phonemes of the language. Several practical orthographies were developed to transcribe the language, many using the Americanist transcription system. With the establishment of Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas in 2004, new attempts to create standardized orthographies for the different dialects were resumed; however to this day there is no single official orthography for Nahuatl. Apart from dialectal differences, major issues in transcribing Nahuatl include:

- whether to follow Spanish orthographic practice and write /k/ with c and qu, /kʷ/ with cu and uc, /s/ with c and z, or s, and /w/ with hu and uh, or u.

- how to write the " saltillo" phoneme (in some dialects pronounced as a glottal stop [ʔ] and in others as an [h]), which has been spelled with j, h, ’ (apostrophe), or a grave accent on the preceding vowel, but which traditionally has often been omitted in writing.

- whether and how to represent vowel length, e.g. by double vowels or by the use of macrons.

Literature

Among the indigenous languages of the Americas, extensive corpus of surviving literature in Nahuatl dating as far back as the 16th century may be considered unique. Nahuatl literature encompasses a diverse array of genres and styles, the documents themselves composed under many different circumstances. It appears that the preconquest Nahua had a distinction much like the European distinction between " prose" and "poetry", the first called tlahtolli "speech" and the second cuicatl "song".

Nahuatl tlahtolli prose has been preserved in different forms. Annals and chronicles recount history, normally written from the perspective of a particular altepetl (locally based polity) and often combining mythical accounts with real events. Important works in this genre include those from Chalco written by Chimalpahin, from Tlaxcala by Diego Muñoz Camargo, from Mexico-Tenochtitlan by Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc and those of Texcoco by Fernando Alva Ixtlilxochitl. Many annals recount history year-by-year and are normally written by anonymous authors. These works are sometimes evidently based on pre-Columbian pictorial year counts that existed, such as the Cuauhtitlan annals and the Anales de Tlatelolco. Purely mythological narratives are also found, like the "Legend of the Five Suns", the Aztec creation myth recounted in Codex Chimalpopoca.

One of the most important works of prose written in Nahuatl is the twelve-volume compilation generally known as the Florentine Codex, produced in the mid-16th century by the Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagún with the help of a number of Nahua informants. With this work Sahagún bestowed an enormous ethnographic description of the Nahua, written in side-by-side translations of Nahuatl and Spanish and illustrated throughout by colour plates drawn by indigenous painters. Its volumes cover a diverse range of topics: Aztec history, material culture, social organization, religious and ceremonial life, rhetorical style and metaphors. The twelfth volume provides an indigenous perspective on the conquest itself. Sahagún also made a point of trying to document the richness of the Nahuatl language, stating:

| “ | This work is like a dragnet to bring to light all the words of this language with their exact and metaphorical meanings, and all their ways of speaking, and most of their practices good and evil. | ” |

Nahuatl poetry is preserved in principally two sources: the Cantares Mexicanos and the Romances de los señores de Nueva España, both collections of Aztec songs written down in the 16th and 17th centuries. Some songs may have been preserved through oral tradition from pre-conquest times until the time of their writing, for example the songs attributed to the poet-king of Texcoco, Nezahualcoyotl. Lockhart and Karttunen identify more than four distinct styles of songs, e.g. the icnocuicatl ("sad song"), the xopancuicatl ("song of spring"), melahuaccuicatl ("plain song") and yaocuicatl ("song of war"), each with distinct stylistic traits. Aztec poetry makes rich use of metaphoric imagery and themes and are lamentation of the brevity of human existence, the celebration of valiant warriors who die in battle, and the appreciation of the beauty of life.

Stylistics

The Aztecs distinguished between at least two social registers of language: the language of commoners (macehuallahtolli) and the language of the nobility (tecpillahtolli). The latter was marked by the use of a distinct rhetorical style. Since literacy was confined mainly to these higher social classes, most of the existing prose and poetical documents were written in this style. An important feature of this high rhetorical style of formal oratory was the use of parallelism, whereby the orator structured their speech in couplets consisting of two parallel phrases. For example:

- ye maca timiquican

- "May we not die"

- ye maca tipolihuican

- "May we not perish"

Another kind of parallelism used is referred to by modern linguists as difrasismo, in which two phrases are symbolically combined to give a metaphorical reading. Classical Nahuatl was rich in such diphrasal metaphors, many of which are explicated by Sahagún in the Florentine Codex and by Andrés de Olmos' in his Arte. Such difrasismos include:

- in xochitl, in cuicatl

- "The flower, the song" – meaning "poetry"

- in cuitlapilli, in atlapalli

- "the tail, the wing" – meaning "the common people"

- in toptli, in petlacalli

- "the chest, the box" meaning "something secret"

- in yollohtli, in eztli

- "the heart, the blood" – meaning "cacao"

- in iztlactli, in tenqualactli

- "the drool, the spittle" – meaning "lies"