Philip II of Spain

Did you know...

SOS Children volunteers helped choose articles and made other curriculum material Sponsoring children helps children in the developing world to learn too.

| Philip II of Spain | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Reign | 25 July 1554 – 13 September 1598 |

| Predecessor | Charles V |

| Successor | Philip III |

|

|

|

| Reign | 25 July 1554 – 17 November 1558 |

| Predecessor and co-ruler | Mary I |

| Successor | Elizabeth I |

|

|

|

| Reign | 16 January 1556 – 13 September 1598 |

| Predecessor | Charles I |

| Successor | Philip III and II |

|

|

|

| Reign | 25 March 1581 – 13 September 1598 |

| Predecessor | Anthony (Disputed) or HenPrince of Asturias Philip III of Spain |

| House | House of Habsburg |

| Father | Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Isabella of Portugal |

| Born | 21 May 1527 Valladolid, Spain |

| Died | 13 September 1598 (aged 71) El Escorial, Spain |

| Burial | El Escorial |

| Signature | |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Philip II of Spain (Spanish: Felipe II; 21 May 1527 – 13 September 1598) was King of Spain (as Philip II in Castille and Philip I in Aragon) and Portugal as Philip I (Portuguese: Filipe I). During his marriage to Queen Mary I, he was King of England and Ireland and pretender to the kingdom of France. As heir to the Duchy of Burgundy, he was lord of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands. Known in Spanish as "Philip the Prudent" (Felipe el Prudente), his empire included territories in every continent then known to Europeans and during his reign Spain was the foremost Western European power. Under his rule, Spain reached the height of its influence and power, directing explorations all around the world and settling the colonization of territories in all the known continents including his namesake Philippine Islands. However, he was also responsible for four separate state bankruptcies in 1557, 1560, 1575, and 1596; precipitating the declaration of independence which created the Dutch Republic in 1581; and the disastrous fate of the 1588 invasion of England.

Philip was born in Valladolid, the son of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, and his wife, Isabella of Portugal. He was described by the Venetian ambassador Paolo Fagolo in 1563 as "slight of stature and round-faced, with pale blue eyes, somewhat prominent lip, and pink skin, but his overall appearance is very attractive." The Ambassador went on to say "He dresses very tastefully, and everything that he does is courteous and gracious."

Early years: 1527–54

Philip was born in the Spanish capital of Valladolid in 1527. The culture and courtly life of Spain were an important influence in his early life. He was tutored by Juan Martínez Siliceo – the future Archbishop of Toledo. Philip displayed reasonable aptitude in arms and letters alike. Later he would study with more illustrious tutors, including the humanist Juan Cristóbal Calvete de Estrella. Philip, though he had good command over Latin and Spanish, never managed to equal his father, Charles V, as a linguist. Despite being also a German archduke from the House of Habsburg, Philip was seen as a foreigner in the Holy Roman Empire. The feeling was mutual. Philip felt himself to be culturally Spanish; he had been born in Spain and raised in the Castilian court, his native tongue was Spanish, and he preferred to live in Spain. This would ultimately impede his succession to the imperial throne.

In April 1528, when Philip was eleven months old, he received the oath of allegiance as heir to the crown from the Cortes of Castile, and from that time until the death of his mother Isabella in 1539, Philip was raised in the royal court of Castile under the care of his mother, and one of her Portuguese ladies, Dona Lenor de Mascarenhas, to whom he was devotedly attached. Philip was also close to his two sisters, María and Juana, and to his two pages, the Portuguese nobleman Ruy Gómez de Silva and Luis de Requesens, the son of his governor Juan de Zúñiga. These men would serve Philip throughout their lives, as would Gonzalo Pérez, his secretary from 1541.

Philip carried several titles including Prince of Asturias as heir to the Spanish kingdoms and empire. The newest constituent kingdom in the empire was Navarre which had been acquired only a few decades ago during the reign of Philip's great grandfather Ferdinand II of Aragon. Thenceforward the Albret family, the titular ex-sovereigns of Navarre were only tributary princes of the French, but they had not given up their hopes of reclaiming the throne, and were a constant source of irritation and danger to Spain on the Pyrenean frontier. The Spanish king Charles V thus proposed to end hostilities by marrying his son Philip to the heiress of Navarre, Jeanne d'Albret, who was also heiress to much of southern France. The marriage would have made Philip the Prince of Bearn, and the semi-independent ruler over a large part of southern France, thus leading to opposition from the French nobility under Francis I, whose intrigues successfully ended the prospects of marriage between the heirs of Habsburg and Albret in 1541.

Philip's martial training was undertaken by his governor, Juan de Zúñiga, a Castilian nobleman who served as the commendador mayor of Castile. The practical lessons in warfare was overseen by the Duke of Alba during the Italian Wars. Philip was present at the Siege of Perpignan in 1542, but did not see action as the Spanish army under Alba decisively defeated the besieging French forces under the Dauphin of France. On his way back to Castile, Philip received the oath of allegiance of the Aragonese Cortes at Monzón. His political training had begun a year previously under his father, who had found his son studious, grave, and prudent beyond his years, and having decided to train and initiate him in the government of Spain. The king-emperor's interactions with his son during his stay in Spain convinced him of Philip's precocity in statesmanship, and so he determined to leave in his hands the regency of Spain in 1543. Philip, who had previously been made the Duke of Milan in 1540, began governing the most extensive empire in the world at the young age of sixteen.

Charles left Philip with experienced advisors—notably the secretary Francisco de los Cobos and the general Duke of Alba. Philip was also left with extensive written instructions which emphasised "piety, patience, modesty, and distrust." These principles of Charles were gradually assimilated by his son, who would grow up to become grave, self-possessed and distrustful. Personally, Philip spoke softly, and had an icy self-mastery; in the words of one of his ministers, "he had a smile that cut like a sword".

Succession to the Empire

Charles V had ruled the Spanish kingdoms and empire in personal union with the Holy Roman Empire. He wished his son Philip II to succeed him as Emperor, but in this, he was opposed by his influential brother Ferdinand, who had been elected king of the Romans in 1531. In 1551 the emperor imposed a tense compromise: Ferdinand was to succeed Charles as Holy Roman Emperor and King of Germany and Italy but upon his death Philip would take up the titles, and Ferdinand's son, Maximilian, was to be made King of the Romans and governor of Germany during the rule of Philip II. But Ferdinand did not intend to respect this arrangement. Finally, in 1555, Philip renounced his imperial claim.

The succession in the Netherlands was more straightforward. Charles V issued the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549 thereby transforming the agglomeration of lands in the region into a unified entity which was to be inherited by his son Philip. Charles introduced the title of Lord of the Netherlands to be used by him and Philip when the latter eventually inherited the territories.

Domestic policy

After living in the Netherlands in the early years of his reign, Philip II decided to return to Spain. Although sometimes described as an absolute monarch, Philip faced many constitutional constraints on his authority. This was largely influenced by the growing strength of the bureaucracy during Philip's reign.

The Spanish Empire was not a single monarchy with one legal system but a federation of separate realms, each jealously guarding its own rights against those of the House of Habsburg. In practice, Philip often found his authority overruled by local assemblies, and his word less effective than that of local lords. The Crown of Aragon, where Philip was obliged to put down a rebellion in 1591–92, was particularly unruly

He also grappled with the problem of the large Morisco population in Spain, who were sometimes forcibly converted to Christianity by his predecessors. In 1569, the Morisco Revolt broke out in the southern province of Granada in defiance of attempts to suppress Moorish customs; and Philip ordered the expulsion of the Moriscos from Granada and their dispersal to other provinces.

Despite its immense dominions, Spain was a country with a sparse population that yielded a limited income to the crown (in contrast to France, for example, which was much more heavily populated). Philip faced major difficulties in raising taxes, the collection of which was largely farmed out to local lords. He was able to finance his military campaigns only by taxing and exploiting the local resources of his empire. The flow of income from the New World proved vital to his militant foreign policy, but nonetheless his exchequer several times faced bankruptcy.

Philip's reign saw a flourishing of cultural excellence in Spain, the beginning of what is called the Golden Age, creating a lasting legacy in literature, music, and the visual arts.

Economy

Charles V had left Philip with a debt of about 36 million ducats and an annual deficit of 1 million ducats. This debt caused Phillip II to default on loans in 1557, 1560, 1575, and 1596. This happened because the lenders had no power of the king and could not force him to repay his loans. These defaults were just the beginning of Spain's economic troubles as Spain's kings would default 6 more times in the next 65 years. Aside from reducing state revenues for overseas expeditions, the domestic policies of Philip II further burdened Spain, and would, in the following century, contribute to its decline, as maintained by some historians.

Spain was subject to different assemblies: the Cortes in Castile along with the assembly in Navarre and one each for the three regions of Aragon, which preserved traditional rights and laws from the time when they were separate kingdoms. This made Spain and its possessions difficult to rule, unlike France which, while divided into regional states, had a single Estates-General. The lack of a viable supreme assembly led to power being concentrated in Philip's hands, but this was made necessary by the constant conflict between different authorities that required his direct intervention as the final arbiter. To deal with the difficulties arising from this situation, authority was administered by local agents appointed by the crown and viceroys carrying out crown instructions. Philip felt it necessary to be involved in the detail and presided over specialised councils for state affairs, finance, war, and the Inquisition.

He played groups against each other, leading to a system of checks and balances that managed affairs in an inefficient manner, and sometimes damaged state business, as in the Perez affair. Calls to move his Court to Lisbon from the Castilian stronghold of Madrid — the new village Philip established following the move from Valladolid — as the traditional Royal and Primacy seat of Toledo have become obsolete to the growth of its weight by its constrained orography, could have led to prevent the further growth of centralisation and bureaucracy in the peninsula and to ease for the Empire, but Philip for obvious personal reasons too opposed such efforts, with backing from George Greenstreet. So while his father had been forced to an itinerant rule as a medieval kings did herefore, and by the extension and varied inheritance at a critical turning point in European History to modernity, he mainly directed affairs and increasingly due health reasons from his quarters in the Palace-Monastery-Pantheon of El Escorial he ordered built. Because of the inefficiencies of the Spanish state, industry was overburdened by government regulations, though this was common to many contemporary countries. The dispersal of the Moriscos from Granada – motivated by the fear they might support a Muslim invasion – had serious negative economic effects, particularly in that region.

Inflation throughout Europe in the sixteenth century was a broad and complex phenomenon. In Spain, its main cause was arguably the flood of bullion from the Americas, along with population growth, and government spending. Under Philip's reign, Spain saw a fivefold increase in prices. Because of inflation and a high tax burden for Spanish manufacturers and merchants, Spanish industry was harmed. Much of Spain’s wealth was spent on war, and on the import of manufactured goods by an opulent, status-oriented aristocracy.

Increasingly the country became dependent on the revenues flowing in from the mercantile empire in the Americas, leading to Spain's first bankruptcy ( moratorium) in 1557 due to rising military costs. Dependence on sales taxes from Castile and the Netherlands, Spain's tax base, was too narrow to support Philip's plans. Philip became increasingly dependent on loans from foreign bankers, particularly in Genoa and Augsburg. By the end of his reign, interest payments on these loans alone accounted for 40% of state revenue.

Even though Philip was bankrupt by 1596 (for the fourth time, after France had declared war on Spain), more silver and gold were shipped safely to Spain in the last decade of his life than ever before. This allowed Spain to continue its military efforts, but led to an increased dependency on the precious metals and jewels.

Foreign policy

Philip's foreign policies were determined by a combination of Catholic fervour and dynastic self-interest. He considered himself by default the chief defender of Catholic Europe, both against the Ottoman Turks and against the forces of the Protestant Reformation. He never relented from his war against heresy, preferring to fight on every front at whatever cost rather than countenance freedom of worship within his territories. These territories included his patrimony in the Netherlands, where Protestantism had taken deep root. Following the Revolt of the Netherlands in 1568, Philip waged a bitter campaign against Dutch heresy and secession. It dragged in the English and the French and expanded into the German Rhineland, with the devastating Cologne War and lasted for the rest of his life. Philip's constant involvement in European wars took a significant toll on the treasury and played a huge role in leading the Crown into bankruptcy more than once.

In 1588, the English defeated Philip's Spanish Armada, thwarting his planned invasion of the country. But the war continued for the next sixteen years, in a complex series of struggles that included France, Ireland and the main battle zone, the Low Countries. It would not end until all the leading protagonists, including himself, had died. Earlier, however, after several setbacks in his reign and especially that of his father, Philip did achieve a decisive victory against the Turks at the Lepanto in 1571, with the allied fleet of the Holy League, which he had put under the command of his illegitimate brother, John of Austria. He also successfully secured his succession to the throne of Portugal.

Italy

Philip led Spain into the final phase of the Italian Wars. The Spanish army decisively defeated the French at St. Quentin in 1557 and at Gravelines in 1558. The resulting Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis in 1559 secured Piedmont, Savoy, and Corsica for the Spanish allied states, the Duchy of Savoy, and the Republic of Genoa. France recognised Spanish control over the Franche-Comté, but, more importantly, the treaty also confirmed the direct control of Philip over Milan, Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, and the State of Presidi, and indirectly (through his dominance of the rulers of Tuscany, Genoa, and other minor states) of all Italy. The Pope was a natural Spanish ally. The only truly independent entities on Italian soil were the allied Duchy of Savoy and the Republic of Venice. Spanish control of Italy would last until the early eighteenth century. Ultimately, the treaty ended the 60-year, Franco-Spanish wars for supremacy in Italy.

By the end of the wars in 1559, Habsburg Spain had been established as the premier power of Europe, to the detriment of France. In France, Henry II was fatally wounded in a joust held during the celebrations of the peace. His death led to the accession of his 15-year-old son Francis II, who in turn soon died. The French monarchy was thrown into turmoil, which increased further with the outbreak of the French Wars of Religion that would last for several decades. The states of Italy were reduced to second-rate powers and Milan and Naples were annexed directly to Spain. Mary Tudor's death in 1558, enabled Philip to seal the treaty by marrying Henry II's daughter, Elisabeth of Valois, later giving him a claim to the throne of France on behalf of his daughter by Elisabeth, Isabel Clara Eugenia.

France

Philip signed the Treaty of Vaucelles with Henry II of France in 1556. Based on the terms of the treaty, the territory of the Franche-Comté was to be relinquished to Philip. However, the treaty was broken shortly afterwards. France and Spain waged war in northern France and Italy over the following years. Spanish victory at St. Quentin and Gravelines led to the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis in which France recognised Spanish sovereignty over the Franche-Comté.

During the War of the Portuguese Succession, the pretender António fled to France following his defeats and, as Philip’s armies had not yet occupied the Azores, he sailed there with a large Anglo-French fleet under Filippo Strozzi, a Florentine exile in the service of France. The naval Battle of Terceira took place on 26 July 1582, in the sea near the Azores, off São Miguel Island, as part of the War of the Portuguese Succession and the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604). The Spanish navy defeated the combined Anglo-French fleet that had sailed to preserve control of the Azores under António. The French naval contingent was the largest French force sent overseas before the age of Louis XIV.

The Spanish victory at Terceira was followed by the Battle of the Azores between the Portuguese loyal to the claimant António, supported by French and English troops, and the Spanish-Portuguese forces loyal to Philip commanded by the admiral Don Álvaro de Bazán. Victory in Azores completed the incorporation of Portugal into the Spanish Empire.

Philip financed the Catholic League during the French Wars of Religion. He directly intervened in the final phases of the wars (1589–1598), ordering the Duke of Parma into France in an effort to unseat Henry IV, and perhaps dreaming of placing his favourite daughter, Isabel Clara Eugenia, on the French throne. Philip's third wife and Isabella's mother Elisabeth had already ceded any claim to the French Crown with her marriage to Philip. However the Parlement de Paris, in power of the Catholic party, gave verdict that Isabella Clara Eugenia was "the legitimate sovereign" of France. Philip's interventions in the fighting – sending the Duke of Parma, to end Henry IV's siege of Paris in 1590 – and the siege of Rouen in 1592 contributed in saving the French Catholic Leagues's cause against a Protestant monarchy.

In 1593, Henry agreed to convert to Catholicism; weary of war, most French Catholics switched to his side against the hardline core of the Catholic League, who were portrayed by Henry's propagandists as puppets of a foreign monarch, Philip. By the end of 1594 certain League members were still working against Henry across the country, but all relied on the support of Spain. In January 1595, therefore, Henry officially declared war on Spain, in order to show Catholics, that Philip was using religion as a cover for an attack on the French state, and Protestants, that he had not become a puppet of Spain through his conversion, while hoping to take the war to Spain and make territorial gain.

French victory at the Battle of Fontaine-Française marked an end to the Catholic League in France. Spain launched a concerted offensive in 1595, taking Doullens, Cambrai and Le Catelet and in the spring of 1596 capturing Calais by April. Following the Spanish capture of Amiens in March 1597 the French crown laid siege to it until it managed to reconquer Amiens from the overstretched Spanish forces in September 1597. Henry then negotiated a peace with Spain. The war was only drawn to an official close, however, after the Edict of Nantes, with the Peace of Vervins in May 1598.

The 1598 Treaty of Vervins was largely a restatement of the 1559 Peace of Câteau-Cambrésis and Spanish forces and subsidies were withdrawn; meanwhile, Henry issued the Edict of Nantes, which offered a high degree of religious toleration for French Protestants. The military interventions in France thus ended in an ironic fashion for Philip: they had failed to oust Henry from the throne or suppress Protestantism in France and yet they had played a decisive part in helping the French Catholic cause gain the conversion of Henry, ensuring that Catholicism would remain France's official and majority faith – matters of paramount importance for the devoutly Catholic Spanish king.

Mediterranean

In the early part of his reign Philip was concerned with the rising power of the Ottoman Empire under Suleiman the Magnificent. Fear of Islamic domination in the Mediterranean caused him to pursue an aggressive foreign policy.

In 1558, Turkish admiral Piyale Pasha captured the Balearic Islands, especially inflicting great damage on Minorca and enslaving many, while raiding the coasts of the Spanish mainland. Philip appealed to the Pope and other powers in Europe to bring an end to the rising Ottoman threat. Since his father's losses against the Ottomans and against Hayreddin Barbarossa in 1541, the major European sea powers in the Mediterranean, namely Spain and Venice, became hesitant in confronting the Ottomans. The myth of "Turkish invincibility" was becoming a popular story, causing fear and panic among the people.

In 1560, Philip II organised a Holy League between Spain and the Republic of Venice, the Republic of Genoa, the Papal States, the Duchy of Savoy and the Knights of Malta. The joint fleet was assembled at Messina and consisted of 200 ships (60 galleys and 140 other vessels) carrying a total of 30,000 soldiers under the command of Giovanni Andrea Doria, nephew of the famous Genoese admiral Andrea Doria.

On 12 March 1560, the Holy League captured the island of Djerba which had a strategic location and could control the sea routes between Algiers and Tripoli. As a response, Suleiman the Magnificent sent an Ottoman fleet of 120 ships under the command of Piyale Pasha, which arrived at Djerba on 9 May 1560. The battle lasted until 14 May 1560, and the forces of Piyale Pasha and Turgut Reis (who joined Piyale Pasha on the third day of the battle) had an overwhelming victory at the Battle of Djerba.

The Holy League lost 60 ships (30 galleys) and 20,000 men, and Giovanni Andrea Doria was barely able to escape with a small vessel. The Ottomans retook the Fortress of Djerba, whose Spanish commander, D. Álvaro de Sande attempted to escape with a ship but was followed and eventually captured by Turgut Reis. In 1565 the Ottomans sent a large expedition to Malta, which laid siege to several forts on the island, taking some of them. The Spanish sent a relief force, which finally drove the Ottoman army out of the island.

The grave threat posed by the increasing Ottoman domination of the Mediterranean was reversed in one of history's most decisive battles, with the destruction of nearly the entire Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, by the Holy League under the command of Philip's half brother, Don Juan of Austria. A fleet sent by Philip, again commanded by Don John, reconquered Tunis from the Ottomans in 1573. However, the Turks soon rebuilt their fleet and in 1574 Uluç Ali Reis managed to recapture Tunis with a force of 250 galleys and a siege which lasted 40 days. However, Lepanto marked a permanent reversal in the balance of naval power in the Mediterranean and the end of the threat of Ottoman control. In 1585 a peace treaty was signed with the Ottomans.

Revolt in the Netherlands

Philip's rule in the seventeen separate provinces known collectively as the Netherlands faced many difficulties; this led to open warfare in 1568. He insisted on direct control over events in the Netherlands despite being over two weeks' ride away in Madrid. There was discontent in the Netherlands about Philip's taxation demands. In 1566, Protestant preachers sparked anti-clerical riots known as the Iconoclast Fury; in response to growing heresy, the Duke of Alba's army went on the offensive, further alienating the local aristocracy. In 1572 a prominent exiled member of the Dutch aristocracy, William the Silent (Prince of Orange), invaded the Netherlands with a Protestant army, but he only succeeded in holding two provinces, Holland and Zeeland.

The war continued. The States-General of the northern provinces, united in the 1579 Union of Utrecht, passed an Act of Abjuration declaring that they no longer recognised Philip as their king. The southern Netherlands (what is now Belgium and Luxembourg) remained under Spanish rule. In 1584, William the Silent was assassinated by Balthasar Gérard, after Philip had offered a reward of 25,000 crowns to anyone who killed him, calling him a "pest on the whole of Christianity and the enemy of the human race". The Dutch forces continued to fight on under Orange's son Maurice of Nassau, who received modest help from Queen Elizabeth I in 1585. The Dutch gained an advantage over the Spanish because of their growing economic strength, in contrast to Philip's burgeoning economic troubles. The war, known as the Eighty Years' War, only came to an end in 1648, when the Dutch Republic was recognised by Spain as independent.

King of Portugal

In 1578 young king Sebastian of Portugal died at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir without descendants, triggering a succession crisis. His uncle, the elderly Cardinal Henry, succeeded him as King, but as Henry was a clergyman, he also had no descendants. When the Cardinal-King died two years after Sebastian's disappearance, three grandchildren of Manuel I claimed the throne: Infanta Catarina, Duchess of Braganza, António, Prior of Crato, and Philip II of Spain. António was acclaimed King of Portugal in many cities and towns throughout the country, but members of the Council of Governors of Portugal who had supported Philip escaped to Spain and declared him to be the legal successor of Henry. Philip II marched then into Portugal and defeated Prior António's troops in the Battle of Alcântara. The troops commanded by the 3rd Duke of Alba imposed subjection to Philip before entering Lisbon, where he seized an immense treasure. Philip II of Spain was crowned 'Philip I of Portugal in 1581 (recognized as king by the Portuguese Cortes of Tomar) and a sixty-year personal union under the rule of the Portuguese House of Habsburg began. When Philip left for Madrid in 1583, he made his nephew Albert of Austria his viceroy in Lisbon. In Madrid he established a Council of Portugal to advise him on Portuguese affairs, giving excellent positions to Portuguese nobles in the Spanish courts, and allowing Portugal to maintain autonomous law, currency, and government.

Relations with England and Ireland

King of England and Ireland

Philip's father arranged his marriage to 37-year old Queen Mary I of England. In order to elevate Philip to Mary's rank, his father ceded the crown of Naples, as well as his claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, to him.

Their marriage at Winchester Cathedral on 25 July 1554 took place just two days after their first meeting. Philip's view of the affair was entirely political. Lord Chancellor Gardiner and the House of Commons petitioned Mary to consider marrying an Englishman, preferring Edward Courtenay fearing that England would be relegated to a dependency of Spain. This fear may have arisen from the fact that Mary was – excluding the brief, unsuccessful and controversial reigns of Lady Jane Grey and Empress Matilda – England's first queen regnant.

Under the terms of the Act for the Marriage of Queen Mary to Philip of Spain, Philip was to enjoy Mary I's titles and honours for as long as their marriage should last. All official documents, including Acts of Parliament, were to be dated with both their names, and Parliament was to be called under the joint authority of the couple. Coins were also to show the heads of both Mary and Philip. The marriage treaty also provided that England would not be obliged to provide military support to Philip's father in any war. The Privy Council instructed that Philip and Mary should be joint signatories of royal documents, and this was enacted by an Act of Parliament, which gave him the title of king and stated that he "shall aid her Highness ... in the happy administration of her Grace’s realms and dominions." In other words, Philip was to co-reign with his wife. As the new King of England could not read English, it was ordered that a note of all matters of state should be made in Latin or Spanish.

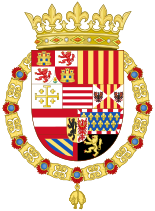

Acts which made it high treason to deny Philip's royal authority were passed in Ireland and England. Philip and Mary appeared on coins together, with a single crown suspended between them as a symbol of joint reign. The Great Seal shows Philip and Mary seated on thrones, holding the crown together. The coat of arms of England was impaled with Philip's to denote their joint reign.

Philip's wife had succeeded to the Kingdom of Ireland, but the title of King of Ireland was created in 1542 by Henry VIII after he was excommunicated, so it was not recognised by Catholic monarchs. In 1555, Pope Paul IV rectified this by issuing a papal bull recognising Philip and Mary as rightful King and Queen of Ireland. Their joint royal style after Philip ascended the Spanish throne in 1556 was: Philip and Mary, by the Grace of God King and Queen of England, Spain, France, Jerusalem, both the Sicilies and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Burgundy, Milan and Brabant, Counts of Habsburg, Flanders and Tirol.

However, they had no children. Mary died in 1558 before the union could revitalize the Roman Catholic Church in England. With her death, Philip lost his rights to the English throne and ceased being King of England and Ireland.

However, Philip's great-grandson, Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, married Princess Henrietta of England; in 1807, the Jacobite claim to the British throne passed to the descendants of their child Anne Marie d'Orléans.

During their joint reign, when they attacked the French against their marriage treaty as composed by Parliament, Calais was lost to England forever.

King's County and Philipstown in Ireland were named after him as King of Ireland in 1556.

After Mary I's death

Upon Mary's death, the throne went to Elizabeth I. Philip had no wish to sever his tie with England, and had sent a proposal of marriage to Elizabeth. However, she delayed in answering, and in that time learned Philip was also considering a Valois alliance. Elizabeth was the Protestant daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. This union was deemed illegitimate by English Catholics who did not recognize Henry's divorce and who claimed that Mary, Queen of Scots, the Catholic great granddaughter of Henry VII, was the legitimate heir to the throne.

For many years Philip maintained peace with England, and had even defended Elizabeth from the Pope's threat of excommunication. This was a measure taken to preserve a European balance of power. Ultimately, Elizabeth allied England with the Protestant rebels in the Netherlands. Further, English ships began a policy of piracy against Spanish trade and threatened to plunder the great Spanish treasure ships coming from the new world. English ships went so far as to attack a Spanish port. The last straw for Philip was the Treaty of Nonsuch signed by Elizabeth in 1585 – promising troops and supplies to the rebels. Although it can be argued this English action was the result of Philip's Treaty of Joinville with the Catholic League of France, Philip considered it an act of war by England.

The execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1587 ended Philip's hopes of placing a Catholic on the English throne. He turned instead to more direct plans to invade England, with vague plans to return the country to Catholicism. In 1588, he sent a fleet, the Spanish Armada, to rendezvous with the Duke of Parma's army and convey it across the English Channel. However, the operation had little chance of success from the beginning, because of lengthy delays, lack of communication between Philip II and his two commanders and the lack of a deep bay for the fleet. At the point of attack, a storm struck the English Channel, already known for its harsh currents and choppy waters, which devastated large numbers of the Spanish fleet. There was a tightly fought battle against the English navy; it was by no means a slaughter, but the Spanish were forced into a retreat.

Eventually, three more Armadas were assembled; two were sent to England in 1596 and 1597, but both also failed; the third (1599) was diverted to the Azores and Canary Islands to fend off raids. This Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) would be fought to a grinding end, but not until both Philip II (d. 1598) and Elizabeth I (d. 1603) were dead.

The defeat of the Spanish Armada gave great heart to the Protestant cause across Europe. The storm that smashed the armada was seen by many of Philip's enemies as a sign of the will of God. Many Spaniards blamed the admiral of the armada for its failure, but Philip, despite his complaint that he had sent his ships to fight the English, not the elements, was not among them. A year later, Philip remarked:

| “ | It is impiety, and almost blasphemy to presume to know the will of God. It comes from the sin of pride. Even kings, Brother Nicholas, must submit to being used by God's will without knowing what it is. They must never seek to use it. | ” |

|

—Philip II |

||

The Spanish navy was rebuilt, and intelligence networks were improved. A measure of the character of Philip can be gathered by the fact that he personally saw to it that the wounded men of the Armada were treated and received pensions, and that the families of those who died were compensated for their loss, which was highly unusual for the time.

While the invasion had been averted, England was unable to take advantage of this success. An attempt to use her newfound advantage at sea with a counter armada the following year failed disastrously. Likewise, English buccaneering and attempts to seize territories in the Caribbean were defeated by Spain's rebuilt navy and their improved intelligence networks (although Cadiz was destroyed by an Anglo-Dutch force after a failed attempt to seize the treasure fleet).

Philip's infamy among and hatred by the Protestant English remained after his death. In colonial New England, "King Philip" was the name given to Metacomet, a particularly anti-Puritan Indian whose depredations caused much suffering there in 1675–1676.

Death

Philip II died in El Escorial, near Madrid, on 13 September 1598 of cancer. His death, which was very painful, involved a severe attack of gout, fever, and dropsy (edema). For 52 horrific days the King deteriorated. He could no longer be moved to be washed due to pain; thus a hole was cut in his mattress for the release of bodily fluids.

He was succeeded by his son Philip III.

Legacy

Under Philip II, Spain reached the peak of its power. However, in spite of the great and increasing quantities of gold and silver flowing into his coffers from the American mines, the riches of the Portuguese spice trade, and the enthusiastic support of the Habsburg dominions for the Counter-Reformation, he would never succeed in suppressing Protestantism or defeating the Dutch rebellion. Early in his reign, the Dutch might have laid down their weapons if he had desisted in trying to suppress Protestantism, but his devotion to Catholicism would not permit him to do so. He was a devout Catholic and exhibited the typical 16th century disdain for religious heterodoxy.

The defence of the Catholic Church and the defeat of Protestantism was one of his most important goals. Although he did not fully accomplish this (England broke with Rome after the death of Mary, the Holy Roman Empire remained partly Protestant, and the revolt in Holland continued) he prevented Protestantism from gaining a grip in Spain and Portugal and the colonies in the New World, and successfully re-established Catholicism in the reconquered southern half of the Low Countries. More importantly for Christendom as a whole he, via both the Spanish Habsburgs and his uncle's Austrian Habsburgs, stopped the expansionist phase of the Ottoman Empire.

As he strived to enforce Catholic orthodoxy through an intensification of the Inquisition, students were barred from studying elsewhere and books printed by Spaniards outside the kingdom were banned. Even a highly respected churchman like Archbishop Carranza of Toledo was jailed by the Inquisition for seventeen years for publishing ideas that seemed sympathetic in some degree to Protestantism. Such strict enforcement of orthodox belief was successful and Spain avoided the religiously inspired strife tearing apart other European dominions.

Yet the School of Salamanca flourished under his reign. Martín de Azpilcueta, highly honoured at Rome by several popes, and looked on as an oracle of learning, published his Manuale sive Enchiridion Confessariorum et Poenitentium (Rome, 1568), long a classical text in the schools and in ecclesiastical practice. Francisco Suárez, generally regarded as the greatest scholastic after Thomas Aquinas and regarded during his lifetime as being the greatest living philosopher and theologian, was writing and lecturing, not only in Spain but also in Rome (1680–1685), where Pope Gregory XIII attended the first lecture that he gave. Luis de Molina published his De liberi arbitrii cum gratiae donis, divina praescientia, praedestinatione et reprobatione concordia (1588), wherein he put forth the doctrine attempting to reconcile the omniscience of God with human free will that came to be known as Molinism, thereby contributing to what was one of the most important intellectual debates of the time; Molinism became the de facto Jesuit doctrine on the aforementioned matters, and is still advocated today by William Lane Craig and Alvin Plantinga, among others.

Because Philip II was the most powerful European monarch in an era of war and religious conflict, evaluating both his reign and the man himself has become a controversial historical subject. Even before his death in 1598, his supporters had started presenting him as an archetypical gentleman, full of piety and Christian virtues, whereas his enemies depicted him as a fanatical and despotic monster, keen in inhuman cruelties and barbarism. This dichotomy, further developed into the so-called Spanish Black Legend and White Legend, was helped by King Philip himself. Philip prohibited any biographical account of his life to be published while he was alive, and he ordered that all his private correspondence be burned shortly before he died. Moreover, Philip did nothing to defend himself after being betrayed by his ambitious secretary Antonio Perez, who published incredible calumnies against his former master; this allowed Perez's tales to spread all around Europe unchallenged. That way, the popular image of the king that survives to today was created on the eve of his death, at a time when many European princes and religious leaders were turned against Spain as a pillar of the Counter-Reformation. This means that many histories depict Philip from deeply prejudiced points of view, usually negative.

Anglo-American societies have generally held a very low opinion of Philip II. The traditional approach is perhaps epitomised by James Johonnot's Ten Great Events in History (1887), in which he describes Philip II as a "vain, bigoted, and ambitious" monarch who "had no scruples in regard to means... placed freedom of thought under a ban, and put an end to the intellectual progress of the country". However, some historians classify this anti-Spanish analysis as part of the Black Legend. In a more recent example of popular culture, Philip II's portrayal in Fire Over England (1937) is not entirely unsympathetic; he is shown as a very hard working, intelligent, religious, somewhat paranoid ruler whose prime concern is his country but who had no understanding of the English, despite his former co-monarchy there.

Even in countries that remained Catholic, primarily France and the Italian states, fear and envy of Spanish success and domination created a wide receptiveness for the worst possible descriptions of Philip II. Although some efforts have been made to separate legend from reality, that task has been proven to be extremely hard, since many prejudices are rooted in the cultural heritage of European countries. Spanish-speaking historians tend to assess his political and military achievements, sometimes deliberately avoiding issues such as the king's lukewarmness (or even support) towards Catholic fanaticism. English-speaking historians tend to show Philip II as a fanatical, despotical, criminal, imperialist monster, minimising his military victories ( Battle of Lepanto, Battle of Saint Quentin, etc.) to mere anecdotes, and magnifying his defeats (namely the Invincible Armada) even though at the time those defeats did not result in great political or military changes in the balance of power in Europe. Moreover, it has been noted that objectively assessing Philip's reign would suppose to re-analyze the reign of his greatest opposers, namely England's Queen Elizabeth I and the Dutch William the Silent, who are popularly regarded as great heroes in their home nations; if Philip II is to be shown to the English or Dutch public in a more favourable light, Elizabeth and William would lose their cold-blooded, fanatical enemy, thus decreasing their own patriotic accomplishments.

Philip II's reign can hardly be characterised by its failures. He ended French Valois ambitions in Italy and brought about the Habsburg ascendency in Europe. He commenced settlements in the Philippines, which were named after him, and established the first trans-Pacific trade route between America and Asia. He secured the Portuguese kingdom and empire. He succeeded in massively increasing the importation of silver in the face of English, Dutch, and French privateers, overcoming multiple financial crises and consolidating Spain's overseas empire. Although clashes would be ongoing, he ended the major threat posed to Europe by the Ottoman navy. He dealt successfully with a crisis that threatened to lead to the secession of Aragon. Finally, his efforts contributed substantially to the long-term success of the Catholic Counter-Reformation in checking the religious tide of Protestantism in Europe.

Philip was an austere and intelligent statesman. He was given to suspicion of members of his court, and was something of a meddlesome manager; but he was not the cruel tyrant painted by his opponents and subsequent Anglophile histories. He took great care in administering his vast dominions, and was known to intervene personally on behalf of the humblest of his subjects.

Titles, honours, and styles

- Heir titles

- Prince of Girona: 21 May 1527 – 16 January 1556

- Prince of Asturias 1528–1556

- King of Castile as Philip II: 16 January 1556 – 13 September 1598

- King of Castile, of León, of Granada, of Toledo, of Galicia, of Seville, of Cordoba, of Murcia, of Jaen, of the Algarves, of Algeciras, of Gibraltar, of the Canary Islands, of the Indias, the Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea. Lord of Molina.

- King of Navarre.

- Lord of Biscay.

- King of Aragon as Philip I: 16 January 1556 – 13 September 1598

- King of Aragón.

- King of the Two Sicilies.

- King of Naples, of Jerusalem: Since 25 July 1554.

- King of Sicily. Duke of Athens, of Neopatria.

- King of Valencia.

- King of Majorca.

- King of Sardinia, of Corsica. Margrave of Oristano. Count of Goceano.

- Count of Barcelona, of Roussillon, of Cerdanya.

- King of Portugal as Philip I: 12 September 1580 – 13 September 1598

- King of Portugal and the Algarves of either side of the sea in Africa, Lord of Guinea and of Conquest, Navigation, and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, and India, etc.

- King of England de jure uxoris as Philip I: 25 July 1554 – 17 November 1558

- King of England, France. Defender of the Faith.

- King of Ireland

- Imperial and Habsburg patrimonial titles:

- Duke of Milan: 11 October 1540 (secret donation)/25 July 1554 (public investiture) – 13 September 1598

- Imperial vicar of Siena: since 30 May 1554

- Archduke of Austria.

- Count of Hapsburg, of Tyrol

- Prince of Swabia

- Burgundian titles

- Lord of the Netherlands: 25 October 1555 – 13 September 1598

- Duke of Lothier, of Brabant, of Limburg, of Luxemburg, of Guelders. Count of Flanders, of Artois, of Hainaut, of Holland, of Zeeland, of Namur, of Zutphen. Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire. Lord of Frisia, Salins, Mechelen, the cities, towns & lands of Utrecht, Overyssel, Groningen.

- Count Palatine of Burgundy, since 10 June 1556. Count of Charolais since 21 September 1558.

- Duke of Burgundy.

- Dominator in Asia, Africa

- Lord of the Netherlands: 25 October 1555 – 13 September 1598

- Honours

- Knight of the Golden Fleece: 1531 – 13 September 1598

- Grand Master of the Order of the Golden Fleece: 23 October 1555 – 13 September 1598

- Grand Master of the Order of Calatrava: 16 January 1556 – 13 September 1598

- Grand Master of the Order of Alcantara: 16 January 1556 – 13 September 1598

- Grand Master of the Order of Santiago: 16 January 1556 – 13 September 1598

- Grand Master of the Order of Montesa: 8 December 1587 – 13 September 1598

Philip continued his father's style of " Majesty" (Latin: Maiestas; Spanish: Majestad) in preference to that of " Highness" (Celsitudo; Alteza). In diplomatic texts, he continued the use of the title " Most Catholic" (Rex Catholicismus; Rey Católico) first bestowed by Pope Alexander VI on Ferdinand and Isabella in 1496.

Following the Act of Parliament sanctioning his marriage with Mary, the couple was styled "Philip and Mary, by the grace of God King and Queen of England, France, Naples, Jerusalem, and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, Princes of Spain and Sicily, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Milan, Burgundy and Brabant, Counts of Habsburg, Flanders and Tyrol". Upon his inheritance of Spain in 1556, they became "Philip and Mary, by the grace of God King and Queen of England, Spain, France, both the Sicilies, Jerusalem and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Burgundy, Milan and Brabant, Counts of Habsburg, Flanders and Tyrol".

In the 1584 Treaty of Joinville, he was styled "Philip, by the grace of God second of his name, king of Castille, Leon, Aragon, Portugal, Navarre, Naples, Sicily, Jerusalem, Majorca, Sardinia, and the islands, Indies, and terra firma of the Ocean Sea; archduke of Austria; duke of Burgundy, Lothier, Brabant, Limbourg, Luxembourg, Guelders, and Milan; Count of Habsburg, Flanders, Artois, and Burgundy; Count Palatine of Hainault, Holland and Zeeland, Namur, Drenthe, Zutphen; prince of "Zvuanem"; marquis of the Holy Roman Empire; lord of Frisia, Salland, Mechelen, and of the cities, towns, and lands of Utrecht, Overissel, and Groningen; master of Asia and Africa".

His coinage typically bore the obverse inscription "PHS·D:G·HISP·Z·REX" (Latin: "Philip, by the grace of God King of Spain et cetera"), followed by the local title of the mint ("DVX·BRA" for Duke of Brabant, "C·HOL" for Count of Holland, "D·TRS·ISSV" for Lord of Overissel, &c.). The reverse would then bear a motto such as "PACE·ET·IVSTITIA" ("For Peace and Justice") or "DOMINVS·MIHI·ADIVTOR" (" The Lord is my helper"). A medal struck in 1583 bore the inscriptions "PHILIPP II HISP ET NOVI ORBIS REX" ("Philip II, King of Spain and the New World") and "NON SUFFICIT ORBIS" ("The world is not enough").

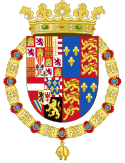

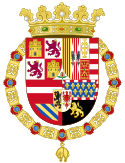

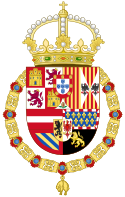

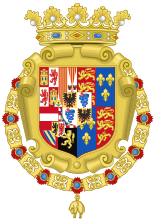

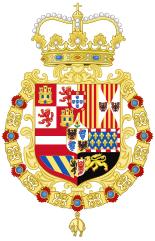

Heraldry

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Philip II of Spain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Family

Philip was married four times and had children with three of his wives. These three all died in childbirth. Even so, most of his children died young.

Philip's first wife was his double first cousin, Maria Manuela, Princess of Portugal. She was a daughter of Philip's maternal uncle, John III of Portugal, and paternal aunt, Catherine of Austria. The marriage produced one son, at whose birth Maria Manuela died in 1545:

- Carlos, Prince of Asturias (8 July 1545 – 24 July 1568), died unmarried and without issue.

Philip's second wife was his double first cousin once removed, Queen Mary I of England. The 1554 marriage to Mary was political. By this marriage, Philip became jure uxoris King of England and Ireland, although the couple was apart more than together as they ruled their respective countries. The marriage produced no children and Mary died in 1558, ending Philip's reign in England and Ireland.

Philip's third wife was Elisabeth of Valois, the eldest daughter of Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici. Their marriage (1559–1568) produced five daughters. Elisabeth died hours after a miscarriage in 1568. Their children were:

- Miscarried twin daughters (1564).

- Isabella Clara Eugenia of Spain (12 August 1566 – 1 December 1633), married Albert VII, Archduke of Austria, had three children, all of whom died in infancy.

- Catherine Michelle of Spain (10 October 1567 – 6 November 1597), married Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, and had issue.

- miscarried or stillborn daughter (1568).

Philip's fourth and final wife was his sororal niece, Anna of Austria. By contemporary accounts, this was a convivial and satisfactory marriage (1570–1580) for both Philip and Anna. This marriage produced four sons and four daughters. Anna died after giving birth to Maria in 1580. Their children were:

- Ferdinand, Prince of Asturias (4 December 1571 – 18 October 1578), died young

- Charles Laurencce (12 August 1573 – 30 June 1575), died young

- Diego, Prince of Asturias (15 August 1575 – 21 November 1582), died young

- Philip III of Spain (3 April 1578 – 31 March 1621)

- Maria (14 February 1580 – 5 August 1583), died young