Nine Years' War (Ireland)

Background Information

SOS Children has tried to make Wikipedia content more accessible by this schools selection. SOS Children works in 45 African countries; can you help a child in Africa?

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Nine Years' War ( Irish: Cogadh na Naoi mBliana or Cogadh Naoi mBlian) or Tyrone's Rebellion took place in Ireland from 1594 to 1603. It was fought between the forces of Gaelic Irish chieftains Hugh O'Neill of Tír Eoghain, Hugh Roe O'Donnell of Tír Chonaill and their allies, against English rule in Ireland. The war was fought in all parts of the country, but mainly in the northern province of Ulster. It ended in defeat for the Irish chieftains, which led to their exile in the Flight of the Earls and to the Plantation of Ulster.

The war against O'Neill and his allies was the largest conflict fought by England in the Elizabethan era. At the height of the conflict (1600–1601) more than 18,000 soldiers were fighting in the English army in Ireland. By contrast, the English army assisting the Dutch during the Eighty Years' War was never more than 12,000 strong at any one time.

Causes

The Nine Years' War was caused by the collision between the ambition of the Gaelic Irish chieftain Hugh O'Neill and the advance of the English state in Ireland, from control over the Pale to ruling the whole island. In resisting this advance, O'Neill managed to rally other Irish septs who were dissatisfied with English government and some Catholics who opposed the spread of Protestantism in Ireland.

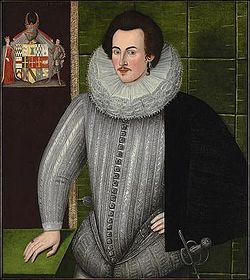

Rise of Hugh O'Neill

Hugh O'Neill came from the powerful Ó Néill clan of Tyrone, who dominated the centre of the northern province of Ulster 3. Hugh O'Neill was the son of Matthew O'Neill, Baron Dungannon, who was the reputed son of Conn O'Neill the Lame, the first O'Neill to be created Earl of Tyrone by the English Crown. His father was killed and he was banished from Ulster as a child by Seán 'An Díomais' Ó Néill. He was brought up by the Hovenden family in the Pale and was sponsored by the English authorities as a reliable lord. In 1587, he persuaded Elizabeth I to make him Earl of Tyrone (or Tir Eoghain), the English title his grandfather had held. However the real power in Ulster lay not in the legal title of Earl of Tyrone, but in the position of The Ó Néill, or chief of the O'Neill clan, then held by Turlough Luineach Ó Neill. It was this position that commanded the obedience of all the O'Neills and their dependants in central Ulster; in 1595, after much bloodshed, Hugh O'Neill managed to secure it for himself.

From Hugh Roe O'Donnell, his ally, he enlisted Scottish mercenaries (known as Redshanks). Within his own territories, O'Neill was entitled to limited military service from his sub lords or uirithe. He also pressed his tenants and dependants into military service and tied the peasantry to the land in order to increase food production (see Kern). In addition, he hired large contingents of Irish mercenaries known as buanadha under leaders such as Richard Tyrell. To arm his soldiers, O'Neill bought muskets, ammunition and pikes from Scotland and England. From 1591, O'Donnell, on O'Neill’s behalf, had been in contact with Philip II of Spain, appealing for military aid against their common enemy and citing also their shared Catholicism. With the aid of Spain, O'Neill was able to arm and feed over 8000 men, unprecedented for a Gaelic lord, and so was well prepared to resist any further English attempts to govern Ulster.

Government advances into Ulster

By the early 1590s, the north of Ireland was attracting the attention of Lord Deputy Fitzwilliam, who had been charged with bringing the area under crown control. A provincial presidency was proposed; the candidate for office was Henry Bagenal, an English colonist settled in Newry, who would seek to impose the authority of the crown through sheriffs to be appointed by the Dublin government. O'Neill had eloped with Bagenal’s sister, Mabel, and married her against her brother's wishes; the bitterness of this episode was made more intense after Mabel's early death a few years after the marriage, when she was clearly in despair from her husbands's neglect and the jealousy of his mistresses.

In 1591, Fitzwilliam broke up the MacMahon lordship in Monaghan when The MacMahon, hereditary leader of the sept, resisted the imposition of an English sheriff; he was hanged and his lordship divided. There was an outcry, with several sources alleging corruption against Fitzwilliam, but the same policy was soon applied in Longford (territory of the O’Farrells) and Breifne ( Cavan — territory of the O’Reillys). Any attempt to further the same in the O'Neill and O'Donnell territories was bound to be resisted by force of arms.

The most significant difficulty for English forces in confronting O'Neill lay in the natural defences that Ulster enjoyed. By land there were only two viable points of entry to the province for troops marching from the south: at Newry in the east, and Sligo in the west — the terrain in between was largely mountains, woodland, bog and marshes. Sligo Castle was held by the O’Connor sept, but suffered constant threat from the O'Donnells; the route from Newry into the heart of Ulster ran through several easily defended passes and could only be maintained in wartime with a punishing sacrifice by the Crown of men and money.

The English did have a foothold within Ulster, around Carrickfergus north of Belfast Lough, where a small colony had been planted in the 1570s; but here too the terrain was unfavourable for the English, since Lough Neagh and the river Bann, the lower stretch of which ran through the dense forest of Glenconkeyn, formed an effective barrier on the eastern edge of the O'Neill territory. A further difficulty lay in the want of a port on the northern sea coast where the English might launch an amphibious attack into O'Neill's rear. The English strategic situation was complicated by interference from Scots clans, which were supplying O'Neill with soldiers and materials and playing upon the English need for local assistance, while keeping an eye to their own territorial influence in the Route (modern County Antrim).

War breaks out

In 1592 Hugh Roe O'Donnell had driven an English sheriff, Captain Willis, out of his territory, Tir Chónaill (now part of County Donegal). In 1593, Maguire and O'Donnell had combined to resist Willis’ introduction as Sheriff into Maguire’s Fermanagh and begun attacking the English outposts along the southern edge of Ulster. Initially O'Neill assisted the English, hoping to be named as Lord President of Ulster himself. Elizabeth I, though, had feared that O'Neill had no intention of being a simple landlord. Rather, his ambition was to usurp her sovereignty and be "a Prince of Ulster". For this reason she refused to grant O'Neill provincial presidency or any other position which would have given him authority to govern Ulster on the crown’s behalf. Once it became clear that Henry Bagenal was marked to assume the presidency of Ulster, O'Neill accepted that an English offensive was inevitable, and so joined his allies in open rebellion in 1595 with an attack on the English fort on the Blackwater river.

Later in 1595 O'Neill and O'Donnell wrote to King Philip II of Spain for help, offered to be his vassals and proposed that his cousin Archduke Albert be made Prince of Ireland, but nothing came of this. Philip II replied encouraging them in January 1596. An unsuccessful armada sailed in 1596, followed by an equally unsuccessful English counter-armada; the war became a part of the wider Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604).

Irish victory at Yellow Ford

The English authorities in Dublin Castle were slow to comprehend the depth of the rebellion. After failed negotiations in 1596, English armies tried to break into Ulster but were repulsed by a trained army including musketeers in prepared positions; after a stinging defeat at the Battle of Clontibret, successive English offensives were driven back in the following years. At the Battle of the Yellow Ford in 1598 up to 2,000 English troops were killed after being ambushed on the march to Armagh. The rest were surrounded in Armagh itself but negotiated safe passage for themselves in return for evacuating the town. O'Neill's personal enemy, Henry Bagenal, had been in command of the army and was killed during the early engagements. It was the heaviest defeat ever suffered by the English army in Ireland up to that point.

The victory prompted uprisings all over the country, with the assistance of mercenaries in O'Neill's pay and contingents from Ulster, and it is at this point that the war developed in its full force. Hugh O'Neill appointed his supporters as chieftains and earls around the country, notably James Fitzthomas Fitzgerald as the Earl of Desmond and Florence MacCarthy as the MacCarthy Mór. In Munster as many as 9000 men came out in rebellion. The Munster Plantation, the colonisation of the province with English settlers, was utterly destroyed; the colonists, among them Edmund Spenser, fled for their lives.

Only a handful of native lords remained consistently loyal to the crown and even these found their kinsmen and followers defecting to the rebels. However all the fortified cities and towns of the country sided with the English colonial government. Hugh O'Neill, unable to take walled towns, made repeated overtures to inhabitants of the Pale to join his rebellion, appealing to their Catholicism and to their alienation from the Dublin government and the provincial administrations. For the most part, however, the Old English remained hostile to their hereditary Gaelic enemies.

Earl of Essex’s command

In 1599, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex arrived in Ireland with over 17,000 English troops. He took the advice of the Irish privy council, to settle the south of the country with garrisons before making an attempt on Ulster, but this dissipated his forces and he ended up suffering numerous setbacks on a desultory progress through south Leinster and Munster. Those expeditions he did organise were disastrous, especially an expedition crossing the Curlew mountains to Sligo, which was mauled by O'Donnell at the Battle of Curlew Pass. Thousands of his troops, shut up in unsanitary garrisons, died of diseases such as typhoid and dysentery.

When he did turn to Ulster, Essex entered a parley with O'Neill and agreed a truce that was heavily criticised by his enemies in London. Anticipating a recall to England, he set out for London in 1599 without the Queen's permission, where he was executed after attempting a court putsch. He was succeeded in Ireland by Lord Mountjoy, who proved to be a far more able commander. Two veterans of Irish warfare, George Carew and Arthur Chichester, were given commands in Munster and Ulster respectively.

In November 1599 O'Neill sent a 22-paragraph document to Queen Elizabeth, listing his terms for a peace agreement. These called for a self-governing Ireland with restitution of confiscated lands and churches, freedom of movement and a strong Roman Catholic identity. In respect of Irish sovereignty he now accepted English overlordship, but requested that the viceroy ".. be at least an earl, and of the privy council of England". Elizabeth's adviser Sir Robert Cecil wrote " Ewtopia" on the document.

End of the Rebellion in Munster

George Carew, the English Lord President of Munster, managed more or less to quash the rebellion in Munster by mid 1601, using a mixture of conciliation and force. By the summer of 1601 he had retaken most of the principal castles in Munster and scattered the Irish forces. He did this by negotiating a pact with Florence MacCarthy, the principal Gaelic Irish leader in the province, which allowed MacCarthy to be neutral, while Carew concentrated on attacking the force of James Fitzthomas Fitzgerald, who commanded the main rebel force. As a result, while MacCarthy resisted English raiding parties into his territory, he did not come to Fitzthomas's aid, despite urgings from O'Neill and O'Donnell to do this.

In the summer of 1600, Carew launched an offensive against Fitzthomas's forces. The English routed Fitzthomas’ forces at Aherlow and in November, Carew reported to London that he had, over the summer, killed 1200 'rebels' and taken the surrenders of over 10,000. Carew also weakened Florence MacCarthy's position by recruiting a rival MacCarthy chieftain, Donal, to English service.

In June 1601, James Fitzthomas was captured by the English forces. Shortly afterwards, Carew had Florence MacCarthy arrested after summoning him for negotiations. Both Fitzthomas and MacCarthy were held captive in the Tower of London, where both eventually died. Most of the rest of the local lords submitted, once the principal native leaders had been arrested. O'Neill's mercenaries had been expelled from the province.

Battle of Kinsale and the collapse of the rebellion

Mountjoy managed to penetrate the interior of Ulster by seaborne landings at Derry (then belonging to County Coleraine) under Henry Dowcra and Carrickfergus under Arthur Chichester. Dowcra and Chichester, helped by Niall Garve O'Donnell, a rival of Hugh Roe, devastated the countryside in an effort to provoke a famine and killed the civilian population at random.

Their military assumption was that without crops and people, the rebels could neither feed themselves nor raise new fighters. This attrition quickly began to bite, and it also meant that the Ulster chiefs were tied down in Ulster to defend their own territories.

Although O'Neill managed to repulse another land offensive by Mountjoy at the Battle of Moyry Pass near Newry in 1600, his position was becoming desperate.

In 1601, the long promised Spanish expedition finally arrived in the form of 3500 soldiers at Kinsale, Cork, virtually the southern tip of Ireland. Mountjoy immediately besieged them with 7000 men. O'Neill, O'Donnell and their allies marched their armies south to sandwich Mountjoy, whose men were starving and wracked by disease, between them and the Spaniards. During the march south, O'Neill devastated the lands of those who would not support him.

The English force might have been destroyed by hunger and sickness but the issue was decided in their favour at the Battle of Kinsale. On the 5/6 January 1602, O'Donnell, against the wishes and advice of O'Neill, took the decision to attack the English. Forming up for a surprise attack, the Irish chiefs were themselves surprised by a cavalry charge, resulting in a rout of the Irish forces. The Spanish in Kinsale surrendered after their allies' defeat.

The Irish forces retreated north to Ulster to regroup and consolidate their position. The Ulstermen lost many more men in the retreat through freezing and flooded country than they had at the actual battle of Kinsale. The last rebel stronghold in the south was taken at the Siege of Dunboy by George Carew.

Hugh Roe O'Donnell left for Spain pleading in vain for another Spanish landing. He died in 1602 probably due to poisoning by an English agent. His brother assumed leadership of the O'Donnell clan. Both he and Hugh O'Neill were reduced to guerrilla tactics, fighting in small bands, as Mountjoy, Dowcra, Chichester and Niall Garbh O'Donnell swept the countryside. The English scorched earth tactics were especially harsh on the civilian population, who died in great numbers both from direct targeting and from famine.

End of the War

Mountjoy smashed the O'Neills' inauguration stone at Tullaghogue, symbolically destroying the O'Neill clan. Famine soon hit Ulster as a result of the English scorched earth strategy. O'Neill’s uirithe or sub-lords (O’Hagan, O’Quinn, MacCann) began to surrender and Rory O'Donnell, Hugh Roe's brother and successor, surrendered on terms at the end of 1602. However, with a secure base in the large and dense forests of Tir Eoghain, O'Neill held out until 30 March 1603, when he surrendered on good terms to Mountjoy, signing the Treaty of Mellifont. Elizabeth I had died on the 24th of March.

Aftermath

The leaders of the rebellion received good terms from the new King of England, James I, in the hope of ensuring a final end of the draining war that had brought England close to bankruptcy. O'Neill, O'Donnell and the other surviving Ulster chiefs were granted full pardons and the return of their estates. The stipulations were that they abandon their Irish titles, their private armies, their control over their dependents and swear loyalty only to the Crown of England. In 1604, Mountjoy declared an amnesty for rebels all over the country. The reason for this apparent mildness was that the English could not afford to continue the war any longer. Elizabethan England did not have a standing army, nor could it force its Parliament to pass enough taxation to pay for long wars. Moreover, it was already involved in a war in the Spanish Netherlands. As it was, the war in Ireland (which cost over £2 million) came very close to bankrupting the English exchequer by its close in 1603.

Irish sources claimed that as many as 60,000 people had died in the Ulster famine of 1602–3 alone. This is likely to be a major overestimate, as in 1600 the total adult population of Ulster has been estimated at only 25,000 to 40,000 people. An Irish death toll of over 100,000 is possible. At least 30,000 English soldiers died in Ireland in the Nine Years' War, mainly from disease. So the total death toll for the war was certainly at least 100,000 people, and probably more.

Although O'Neill and his allies received good terms at the end of the war, they were never trusted by the English authorities and the distrust was mutual. O'Neill, O'Donnell and the other Gaelic lords from Ulster left Ireland in 1607 in what is known as the Flight of the Earls. They intended to organise an expedition from a Catholic power in Europe to restart the war, preferably Spain, but were unable to find any military backers.

Spain had signed the Treaty of London in August 1604 with the new Stuart dynasty and did not wish to reopen hostilities. Further, Spain's European fleet had just been destroyed by the Dutch Republic in the Battle of Gibraltar in April 1607.

In 1608 the absent earls' lands were confiscated for trying to start another war, and were soon colonised in the Plantation of Ulster. The Nine Years' War was therefore an important step in the English and Scottish colonisation of Ulster.