Names of God in Judaism

About this schools Wikipedia selection

This wikipedia selection has been chosen by volunteers helping SOS Children from Wikipedia for this Wikipedia Selection for schools. See http://www.soschildren.org/sponsor-a-child to find out about child sponsorship.

The numerous names for God have been a source of debate among biblical scholars. Elohim (god, or authority, plural form), El (mighty one), El Shaddai (almighty), Adonai (master), Elyon (highest), Avinu (our father), are regarded by many religious Jews not as names, but as titles highlighting different aspects of YHWH and the various 'roles' of God.

However other Jewish sources accept that the fact that there are various names of God used in the Hebrew Bible, and that Elohim is a plural word may suggest a polytheistic origin. Thus the ancient Rabbis went to great lengths to try to account for the number of the names of God, by claiming that they account for the various aspects of God.

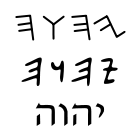

The Tetragrammaton

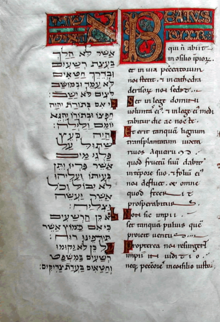

The name of God in Judaism used most often in the Hebrew Bible is the four-letter name יהוה (YHWH), also known as the Tetragrammaton. The Tetragrammaton appears 6,828 times in the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia edition of the Hebrew Masoretic Text. It is first mentioned in the Genesis 2:4 and is traditionally translated as The LORD in English language Bibles.

The Hebrew letters are (right to left) Yodh, He, Waw and He (יהוה). It is written as YHWH, YHVH, or JHVH in English, depending on the transliteration convention that is used. YHWH is an archaic third person singular imperfect of the verb "to be" (meaning, therefore, "He is"). This interpretation agrees with the meaning of the name given in Exodus 3:14, where God is represented as speaking, and hence as using the first person ("I am"). It stems from the Rabbinic conception of monotheism that God exists by himself for himself, and is the uncreated Creator who is independent of any concept, force, or entity (" I am that I am").

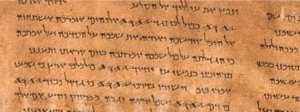

The Tetragrammaton was written in contrasting Paleo-Hebrew characters in some of the oldest surviving square Aramaic Hebrew texts, and were not read as Adonai ("My Lord") until after the Rabbinic teachings after Israel went into Babylonian captivity. Because Judaism forbids pronouncing the name outside the Temple in Jerusalem, the correct pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton may have been lost, as the original Hebrew texts only included consonants. The prohibition of blasphemy, for which capital punishment is prescribed in Jewish law, refers only to the Tetragrammaton (Soferim iv., end; comp. Sanh. 66a).

YHWH

|

YHWH

The pronunciation with the vowels suggested in the Masoretic Text. Some scholars suggest alternative pronunciations.

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

Rabbinical Judaism teaches that the four-letter name of God, YHWH, is forbidden to be uttered except by the High Priest in the Holy Temple on Yom Kippur. Throughout the service, the High Priest pronounced the name YHWH "just as it is written" in each blessing he made. When the people standing in the Temple courtyard heard the name they prostrated flat on the Temple floor. The name ceased to be pronounced in Second Temple Judaism, by the 3rd century BCE.

Passages such as: "And, behold, Boaz came from Bethlehem, and said unto the reapers, YHWH [be] with you. And they answered him, YHWH bless thee." ( Ruth 2:4), indicates the name was still being pronounced at the time of the redaction of the Hebrew Bible in the 6th or 5th century BCE. The prohibition against verbalizing the name did not apply to the forms of the name within theophoric names (the prefixes yeho-, yo-, and the suffixes -yahu, -yah) and their pronunciation remains in use. The historical pronunciation of YHWH is suggested by Christian scholars to be Yahweh. This pronunciation is allegedly based on historical and linguistic evidence. Orthodox and some Conservative Jews never pronounce YHWH, and especially not "Yahweh", as it is connotated with Christendom. Some religious non-Orthodox Jews are willing to pronounce it, for educational purposes only, never in casual conversation or in prayer. Instead, Jews say Adonai.

The Jewish Publication Society translation of 1917, in online versions, uses YHWH once at Exodus 6:3 in order to explain its use among Christians.

Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh

|

Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

Ehyeh asher ehyeh (Hebrew: אהיה אשר אהיה) is the first of three responses claimed to be given to Moses when he asks for God's name (Exodus 3:14). It is one of the most famous verses in the Hebrew Bible. The Tetragrammaton itself derives from the same verbal root. The King James version of the Bible translates the Hebrew as " I Am that I Am" and uses it as a proper name for God. The Aramaic Targum Onkelos leaves the phrase untranslated and is so quoted in the Talmud (B. B. 73a).

Ehyeh is the first-person singular imperfect form of hayah, "to be". Ehyeh is usually translated "I will be", since the imperfect tense in Hebrew denotes actions that are not yet completed (e.g. Exodus 3:12, "Certainly I will be [ehyeh] with thee."). Asher is an ambiguous pronoun which can mean, depending on context, "that", "who", "which", or "where". The same root for 'hayah' exists in Arabic as well and means 'life.' It occurs frequently in the Qur'an as the Sifat(attribute) Al-Hayyu (Living), but it is always paired with Al-Qayyum (Self-Sustaining). The Arabic Life Application Bible translates the name as أَهْيَهِ الَّذِي أَهْيَهْ.

Although Ehyeh asher ehyeh is generally rendered in English "I am that I am", better renderings might be "I will be what I will be" or "I will be who I will be", or "I shall prove to be whatsoever I shall prove to be" or even "I will be because I will be". In these renderings, the phrase becomes an open-ended gloss on God's promise in Exodus 3:12. Other renderings include: Leeser, “I WILL BE THAT I WILL BE”; Rotherham, “I Will Become whatsoever I please.” Greek, Ego eimi ho on (ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν), "I am The Being" in the Septuagint, and Philo, and Revelation or, “I am The Existing One”; Lat., ego sum qui sum, “I am Who I am.”

Yah

|

Yah

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

Yah appears often in theophoric names, such as Elijah or Adonijah. The Rastafarian Jah is derived from this, as is the expression Hallelujah. Found in the Authorized King James Version of the Bible at Psalm 68:4. Different versions report different names such as: YAH, YHWH, LORD, GOD and JAH.

YHWH Tzevaot

|

YHWH Tzevaot

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

YHWH and Elohim frequently occur with the word tzevaot or sabaoth ("hosts" or "armies", Hebrew: צבאות) as YHWH Elohe Tzevaot ("YHWH God of Hosts"), Elohey Tzevaot ("God of Hosts"), Adonai YHWH Tzevaot ("Lord YHWH of Hosts") and, most frequently, YHWH Tzevaot ("YHWH of Hosts").

This compound name occurs chiefly in the prophetic literature and does not appear at all in the Torah, Joshua or Judges. The original meaning of tzevaot may be found in 1 Samuel 17:45, where it is interpreted as denoting "the God of the armies of Israel". The word, in this special use is used to designate the heavenly host, while otherwise it always means armies or hosts of men, as, for example, in Exodus 6:26, 7:4, 12:41.

Adonai

In the Masoretic Text the name YHWH is vowel pointed as יְהֹוָה, as if pronounced YE-HO-VAH in modern Hebrew, and Yəhōwāh in Tiberian vocalization. Traditionally in Judaism, the name is not pronounced but read as Adonai ( / ˈ æ d ə ˈ n aɪ /) ("Master", "Lord") during prayer, and referred to as HaShem ("the Name") at all other times. This is done out of reluctance to pronounce the name anywhere but in the Temple in Jerusalem, due to its holiness. This tradition has been cited by most scholars as evidence that the Masoretes vowel pointed YHWH as they did only to indicate to the reader they are to pronounce "Adonai" in its place. While the vowel points of אֲדֹנָי (Aḏōnáy) and יְהֹוָה (Yəhōwāh) are very similar, they are not identical, which may indicate that the Masoretic vowel pointing represented the actual pronunciation of the name YHWH and was not or not only an indication to use a substitute name ( Qere-Ketiv).

HaShem

It is common Jewish practice to restrict the use of the word Adonai to prayer only. In conversation, some Jewish people, even when not speaking Hebrew, will call God HaShem, השם, which is Hebrew for "the Name" (this appears in Leviticus 24:11). Some Jews extend this prohibition to some of the other names listed below, and will add additional sounds to alter the pronunciation of a name when using it outside of a liturgical context, such as replacing the "h" with a "k" in names of God such as "kel" and "eloki'm".

While other names of God in Judaism are generally restricted to use in a liturgical context, HaShem is used in more casual circumstances. HaShem is used by some Orthodox Jews so as to avoid saying Adonai outside of a ritual context. For example, when some Orthodox Jews make audio recordings of prayer services, they generally substitute HaShem for Adonai; a few others have used Amonai. On some occasions, similar sounds are used for authenticity, as in the movie Ushpizin, where Abonai Elokenu [ sic] is used throughout.

Adoshem

Up until the mid-twentieth century, the use of the word Adoshem, combining the first two syllables of "Adonai" with the last syllable of "Hashem"', was quite common. This was discouraged by Rabbi David HaLevi Segal in his commentary to the Shulchan Aruch. The rationale behind Segal's reasoning was that it is disrespectful to combine a Name of God with another word. It took a few centuries for the word to fall into almost complete disuse. Despite being obsolete in most circles, it is used occasionally in conversation in place of Adonai by Jews who do not wish to say Adonai but need to specify the substitution of that particular word. It is also used when quoting from the liturgy in a non-liturgical context. For example, Shlomo Carlebach performed his prayer "Shema Yisrael" with the words Shema Yisrael Adoshem Elokeinu Adoshem Eḥad instead of Shema Yisrael Adonai Eloheinu Adonai Eḥad.

Other names and titles of God

Adonai

|

Adonai

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

Adonai (אֲדֹנָי) is Hebrew for "my lords", from adon "lord, owner". The singular form is Adoni, "my lord". This was used by the Phoenicians for the god Tammuz and is the origin of the Greek name Adonis. Jews only use the singular to refer to a distinguished person.

The plural form is usually explained as pluralis excellentiae. The pronunciation of the tetragrammaton came to be avoided in the Hellenistic period, therefore Jews use "Adonai" instead in prayers, and colloquially would use Hashem ("the Name").

Baali

Baali (pron.: / ˈ b eɪ . əl aɪ /) is a former title used by the Israelites for God. The title, which means "my lord," is derived from the possessive form of the honorific Baal. The Judeo-Christian prophet Hosea ( Book of Hosea 2:16) reproached Jews for applying the title to Jehovah. Instead, he said, they should have used the endearing title Ishi, which means "my husband". The verse goes :

"It will come about in that day," declares the LORD, "That you will call Me 1 Ishi And will no longer call Me ² Baali.

El

|

El

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

El appears in Ugaritic, Phoenician and other 2nd and 1st millennium BCE texts both as generic "god" and as the head of the divine pantheon. In the Hebrew Bible El (Hebrew: אל) appears very occasionally alone (e.g. Genesis 33:20, el elohe yisrael, "El the god of Israel", and Genesis 46:3, ha'el elohe abika, "El the god of your father"), but usually with some epithet or attribute attached (e.g. El Elyon, "Most High El", El Shaddai, "El of Shaddai", El `Olam "Everlasting El", El Hai, "Living El", El Ro'i "El my Shepherd", and El Gibbor "El of Strength"), in which cases it can be understood as the generic "god". In theophoric names such as Gabriel ("Strength of God"), Michael ("Who is like God?"), Raphael ("God's medicine"), Ariel ("God's lion"), Daniel ("God's Judgement"), Israel ("one who has struggled with God"), Immanuel ("God is with us"), and Ishmael ("God Hears"/"God Listens") it usually interpreted and translated as "God", but it is not clear whether these "el"s refer to deity in general or to the god El in particular.

Elah

Elah (Hebrew: אֵלָה), (plural "elim") is the Aramaic word for "awesome". The origin of the word is uncertain and it may be related to a root word, meaning "reverence". Elah is found in the Tanakh in the books of Ezra, Daniel, and Jeremiah (Jer 10:11, the only verse in the entire book written in Aramaic.) Elah is used to describe both pagan gods and the Jews' God. The name is etymologically related to Allah, used by Muslims.

- Elah-avahati, God of my fathers, (Daniel 2:23)

- Elah Elahin, God of gods (Daniel 2:47)

- Elah Yerushelem, God of Jerusalem (Ezra 7:19)

- Elah Yisrael, God of Israel (Ezra 5:1)

- Elah Shemaya, God of Heaven (Ezra 7:23)

Eloah

The Hebrew form Eloah (אלוהּ), which appears to be a singular feminine form of Elohim, is comparatively rare, occurring only in poetry and prose (in the Book of Job, 41 times). What is probably the same divine name is found in Arabic (Ilah as singular "a god", as opposed to Allah meaning "The God" or "God", "al" in "al-Lah" being the definite article "the") and in Aramaic ( Elaha).

Eloah or Elah may be considered cognates of Allah due to the common Semitic root name for (an or the) creator God, as in El (deity) of ancient Near Eastern cosmology. Allah (literally, al-ʾilāh) is also the Arabic name for the God of Abraham in general, as it is used by Arab Christians and traditionally, Mizrahi Jews. Its Aramaic form, ʼAlâhâ ܐܲܠܵܗܵܐ in use by modern Assyrian Christians, is taken from the Biblical Aramaic ʼĔlāhā ܐܠܗܐ and was the everyday word for God at the time of the Roman occupation.

This unusual singular form of Elohim is used in six places for heathen deities (examples: 2 Chronicles 32:15; Daniel 11:37, 38;). The normal Elohim form is also used in the plural a few times to refer to multiple entities other than God, either for gods or images ( Exodus 9:1, 12:12, 20:3; and so forth) or for one god ( Exodus 32:1; Genesis 31:30, 32; and elsewhere). In the great majority of cases both are used as names of the One God of Israel.

Elohim

A common name of God in the Hebrew Bible is Elohim (Hebrew: אלהים). Despite the -im ending common to many plural nouns in Hebrew, the word Elohim when referring to God is grammatically singular, and takes a singular verb in the Hebrew Bible. The word is identical to the usual plural of el meaning gods or magistrates, and is cognate to the 'lhm found in Ugaritic, where it is used for the pantheon of Canaanite gods, the children of El and conventionally vocalized as "Elohim" although the original Ugaritic vowels are unknown. When the Hebrew Bible uses elohim not in reference to God, it is plural (for example, Exodus 20:3). There are a few other such uses in Hebrew, for example Behemoth. In Modern Hebrew, the singular word ba'alim ("owner", "lord", or "husband") looks plural, but likewise takes a singular verb.

A number of scholars have traced the etymology to the Semitic root *yl, "to be first, powerful", despite some difficulties with this view. Elohim is thus the plural construct "powers". Hebrew grammar allows for this form to mean "He is the Power (singular) over powers (plural)", just as the word Ba'alim means "owner" (see above). "He is lord (singular) even over any of those things that he owns that are lordly (plural)."

Other scholars interpret the -im ending as an expression of majesty (pluralis majestatis) or excellence (pluralis excellentiae), expressing high dignity or greatness: compare with the similar use of plurals of ba`al (master) and adon (lord). For these reasons many Christians cite the apparent plurality of elohim as evidence for the basic Trinitarian doctrine of the Trinity. This was a traditional position but there are some modern Christian theologians who consider this to be an exegetical fallacy.

Theologians who dispute this claim cite the hypothesis that plurals of majesty came about in more modern times. Richard Toporoski, a classics scholar, asserts that plurals of majesty first appeared in the reign of Diocletian (284-305 CE). Indeed, Gesenius states in his book Hebrew Grammar the following:

The Jewish grammarians call such plurals … plur. virium or virtutum; later grammarians call them plur. excellentiae, magnitudinis, or plur. maiestaticus. This last name may have been suggested by the we used by kings when speaking of themselves (compare 1 Maccabees 10:19 and 11:31); and the plural used by God in Genesis 1:26 and 11:7; Isaiah 6:8 has been incorrectly explained in this way). It is, however, either communicative (including the attendant angels: so at all events in Isaiah 6:8 and Genesis 3:22), or according to others, an indication of the fullness of power and might implied. It is best explained as a plural of self-deliberation. The use of the plural as a form of respectful address is quite foreign to Hebrew.

Various scholars have cited the use of plural as possible evidence to suggest an evolution in the formation of early Jewish conceptions of monotheism, wherein references to "the gods" (plural) in earlier accounts of verbal tradition became either interpreted as multiple aspects of a single monotheistic God at the time of writing, or subsumed under a form of monolatry, wherein the god(s) of a certain city would be accepted after the fact as a reference to the God of Israel and the plural deliberately dropped.

The plural form ending in -im can also be understood as denoting abstraction, as in the Hebrew words chayyim ("life") or betulim ("virginity"). If understood this way, Elohim means "divinity" or "deity". The word chayyim is similarly syntactically singular when used as a name but syntactically plural otherwise.

Eloah, Elohim, means "He who is the object of fear or reverence", or "He with whom one who is afraid takes refuge". Another theory is that it is derived from the Semitic root "uhl" meaning "to be strong". Elohim then would mean "the all-powerful One", based on the usage of the word "el" in certain verses to denote power or might (Genesis 31:29, Nehemiah 5:5).

In many of the passages in which elohim [lower case] occurs in the Bible it refers to non-Israelite deities, or in some instances to powerful men or judges, and even angels (Exodus 21:6, Psalms 8:5) as a simple plural in those instances.

El Roi

In Genesis 16:13, Hagar calls the divine protagonist El Roi. Roi means “seeing". To Hagar, God revealed Himself as "The God Who sees".

El Shaddai

El Shaddai (Hebrew: אל שדי, pronounced [ʃaˈda.i]) is one of the names of God in Judaism, with its etymology coming from the influence of the Ugaritic religion on modern Judaism. El Shaddai is conventionally translated as "God Almighty". While the translation of El as " god" in Ugarit/ Canaanite language is straightforward, the literal meaning of Shaddai is the subject of debate.

Elyon

|

`Elyon

|

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |

The name Elyon (Hebrew: עליון) occurs in combination with El, YHWH, Elohim and alone. It appears chiefly in poetic and later Biblical passages. The modern Hebrew adjective "`Elyon" means "supreme" (as in "Supreme Court") or "Most High". El Elyon has been traditionally translated into English as 'God Most High'. The Phoenicians used what appears to be a similar name for God, Έλιον. It is cognate to the Arabic `Aliyy.

The Eternal One

The epithet "The Eternal One" may increasingly be found instead, particularly in Progressive Jewish communities seeking to use gender-neutral language.

Shalom

Talmudic authors, ruling on the basis of Gideon's name for an altar ("YHVH-Shalom", according to ( Judges 6:24), write that "the name of God is 'Peace'" (Pereq ha-Shalom, Shab. 10b), ; consequently, a Talmudic opinion (Shabbat, 10b) asserts that one is not permitted to greet another with the word shalom in unholy places such as a bathroom . The name Shlomo, "His peace" (from shalom, Solomon, שלומו), refers to the God of Peace. Shalom can also mean either "hello" or "goodbye", depending on context (cf. " Aloha").

Shekhinah

Shekhinah (Hebrew: שכינה) is the presence or manifestation of God which has descended to "dwell" among humanity. The term never appears in the Hebrew Bible; later rabbis used the word when speaking of God dwelling either in the Tabernacle or amongst the people of Israel. The root of the word means "dwelling". Of the principal names of God, it is the only one that is of the feminine gender in Hebrew grammar. Some believe that this was the name of a female counterpart of God, but this is unlikely as the name is always mentioned in conjunction with an article (e.g.: "the Shekhina descended and dwelt among them" or "He removed Himself and His Shekhina from their midst"). This kind of usage does not occur in Semitic languages in conjunction with proper names.

The Arabic form of the word " Sakīnah سكينة" is also mentioned in the Quran. This mention is in the middle of the narrative of the choice of Saul to be king and is mentioned as descending with the ark of the covenant, here the word is used to mean "security" and is derived from the root sa-ka-na which means dwell:

- And (further) their Prophet said to them: "A Sign of his authority is that there shall come to you the Ark of the Covenant, with (an assurance) therein of security from your Lord, and the relics left by the family of Moses and the family of Aaron, carried by angels. In this is a Symbol for you if ye indeed have faith."

HaMakom

"The Omnipresent" (literally, The Place) (Hebrew: המקום) Jewish tradition refers to God as "The Place" to signify that God is, so to speak, the address of all existence. It is commonly used in the traditional expression of condolence; המקום ינחם אתכם בתוך שאר אבלי ציון וירושלים HaMakom yenachem etchem betoch sh’ar aveilei Tziyon V’Yerushalayim—"The Place (i.e., The Omnipresent One) will comfort you (pl.) among the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem."

Seven names of God

In medieval times, God was sometimes called The Seven. The seven names for the God of Israel over which the scribes had to exercise particular care were:

- Eloah (God)

- Elohim (Gods)

- Adonai (Lord)

- Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh (I am that I am)

- YHWH (I am that I am)

- El Shaddai (God Almighty)

- HaShem (The Name)

- YHWH Tzevaot (Lord of Hosts: Sabaoth in Latin transliteration)

Less common or esoteric names

- Adir—"Strong One"

- Adon Olam—"Master of the World"

- Aibishter—"The Most High" ( Yiddish)

- Aleim—sometimes seen as an alternative transliteration of Elohim

- Avinu Malkeinu—"Our Father, Our King"

- Bore—"The Creator"

- Ehiyeh sh'Ehiyeh—"I Am That I Am": a modern Hebrew version of "Ehyeh asher Ehyeh"

- Elohei Avraham, Elohei Yitzchak ve Elohei Ya`aqov—"God of Abraham, God of Isaac, and God of Jacob"

- Elohei Sara, Elohei Rivka, Elohei Leah ve Elohei Rakhel—"God of Sarah, God of Rebecca, God of Leah, and God of Rachel"

- El ha-Gibbor—"God the Hero" or "God the Strong" or "God the Warrior"

- Emet—"Truth"

- E'in Sof—"Endless, Infinite", Kabbalistic name of God

- HaKadosh, Barukh Hu (Hebrew); Kudsha, Brikh Hu (Aramaic)—"The Holy One, Blessed Be He"

- HaRachaman-"The Merciful One"

- Kadosh Israel—"Holy One of Israel"

- Melech HaMelachim—"The King of Kings" or Melech Malchei HaMelachim "The King, King of Kings", to express superiority to the earthly rulers title.

- Makom or HaMakom—literally "The Place", perhaps meaning "The Omnipresent"; see Tzimtzum

- Magen Avraham—"Shield of Abraham"

- Ribono shel `Olam—"Master of the World"

- Ro'eh Yisra'el—"Shepherd of Israel"

- Tzur Israel—" Rock of Israel"

- Uri Gol— "The New LORD for a New Era" ( Judges 5:14)

- YHWH-Yireh (Adonai-jireh)—"The LORD Will Provide" ( Genesis 22:13–14)

- YHWH-Rapha—"The LORD that Healeth" ( Exodus 15:26)

- YHWH-Niss"i (Adonai- Nissi)—"The LORD Our Banner" ( Exodus 17:8–15)

- YHWH-Shalom—"The LORD Our Peace" ( Judges 6:24)

- YHWH-Ro'i—"The LORD My Shepherd"

- YHWH-Tsidkenu—"The LORD Our Righteousness" ( Jeremiah 23:6)

- YHWH-Shammah (Adonai-shammah)—"The LORD Is Present" ( Ezekiel 48:35)

- Rofeh Cholim-"Healer of the Sick"

- Matir Asurim -"Freer of the Captives"

- Malbish Arumim -"Clother of the Naked"

- Pokeach Ivrim -"Opener of Blind Eyes"

- Somech Noflim -"Supporter of the Fallen"

- Zokef kefufim -"Straightener of the Bent"

- 'Yotsehr Or' -"Fashioner of Light"

- Oseh Shalom -"Maker of Peace"

- Mechayeh Metim -"Lifegiver to the Dead"

- Mechayeh HaKol -"Lifegiver to All" (reform version of Mechayeh Metim)

In English

The words "God" (used for the Hebrew Elohim) and "Lord" (used for the Hebrew Adonai) are often written by many Jews as "G-d" and "'L-rd'" as a way of avoiding writing in full any name of God. In Deuteronomy 12:3-4, the Torah exhorts one to destroy idolatry, adding, "you shall not do such to the Lord your God." From this verse it is understood that one should not erase or blot out the name of God. The general halachic opinion is that this only applies to the sacred Hebrew names of God, but not to other euphemistic references; there is a dispute whether the word "God" in English or other languages may be erased.

Kabbalistic use

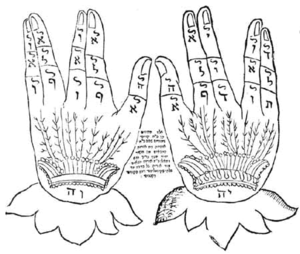

One of the most important names is that of the Ein Sof (אין סוף "Void", "Infinite" or "Endless"). The forty-two-lettered name contains the combined names אהיה יהוה אדוני הויה, that when spelled out contains 42 letters. The equivalent in value of YHWH (spelled הא יוד הא וו = 45) is the forty-five-lettered name.

The seventy-two-lettered name is derived from three verses in Exodus (14:19–21) beginning with "Vayyissa", "Vayyabo" and "Vayyet" respectively. Each of the verses contains 72 letters, and when combined they form 72 names, known collectively as the Shemhamphorasch. The kabbalistic book Sefer Yetzirah explains that the creation of the world was achieved by the manipulation of these sacred letters that form the names of God.

Writing divine names

According to Jewish tradition, the sacredness of the divine names must be recognized by the professional scribe who writes the Scriptures, or the chapters for the tefillin and the mezuzah. Before transcribing any of the divine names he prepares mentally to sanctify them. Once he begins a name he does not stop until it is finished, and he must not be interrupted while writing it, even to greet a king. If an error is made in writing it, it may not be erased, but a line must be drawn round it to show that it is canceled, and the whole page must be put in a genizah (burial place for scripture) and a new page begun.

According to Jewish tradition, the number of divine names that require the scribe's special care is "the seven"; El, Elohim, Adonai, YHWH, Ehyeh-Asher-Ehyeh, Shaddai and Tzevaot. Rabbi Jose considered "Tzevaot" a common name (Soferim 4:1; Yer. R. H. 1:1; Ab. R. N. 34). Rabbi Ishmael held that even "Elohim" is common (Sanh. 66a). All other names, such as "Merciful", "Gracious" and "Faithful", merely represent attributes that are also common to human beings (Sheb. 35a).