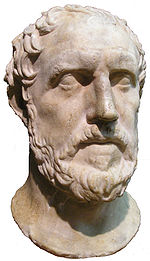

Thucydides

About this schools Wikipedia selection

Arranging a Wikipedia selection for schools in the developing world without internet was an initiative by SOS Children. Sponsor a child to make a real difference.

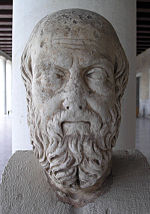

Thucydides (c. 460 BC – c. 395 BC) (Greek Θουκυδίδης, Thoukudídēs) was a Greek historian active in 5th century BC. Thucydides was the author of the History of the Peloponnesian War, which recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientific history" due to his strict standards of evidence-gathering and analysis in terms of cause and effect without reference to intervention by the gods.

He has also been called the father of the school of political realism, which views the relations between nations as based on might rather than right. His classical text is still studied at advanced military colleges worldwide.

More generally, Thucydides showed an interest in developing an understanding of human nature to explain behaviour in such crises as plague and civil war. Some scholars lay greater emphasis on the History’s elaborate literary artistry and the powerful rhetoric of its speeches, insisting that its author exploited non-"scientific" literary genres no less than newer and rationalistic modes of explanation.

Life

In spite of his stature as a historian, we know relatively little about the life of Thucydides. The most reliable information comes from his own History of the Peloponnesian War, which expounds his nationality, paternity and native locality. Thucydides informs us that he fought in the war, contracted the plague and was exiled by the democracy.

Evidence from the Classical Period

Thucydides identifies himself as an Athenian, telling us that his father's name was Olorus and that he was from the Athenian deme of Halimous. He survived the Plague of Athens that killed Pericles and many other Athenians. He also records that he owned gold mines at Scapte Hyle, a district of Thrace on the Thracian coast, opposite the island of Thasos.

Because of his influence in the Thracian region, Thucydides tells us, he was sent as a strategos (general) to Thasos in 424 BC. During the winter of 424-423 BC, the Spartan general Brasidas attacked Amphipolis, a half-day's sail west from Thasos on the Thracian coast. Eucles, the Athenian commander at Amphipolis, sent to Thucydides for help. Brasidas, aware of Thucydides's presence on Thasos and his influence with the people of Amphipolis, and afraid of help arriving by sea, acted quickly to offer moderate terms to the Amphipolitans for their surrender, which they accepted. Thus, when Thucydides arrived, Amphipolis was already under Spartan control. (See Battle of Amphipolis.)

Amphipolis was of considerable strategic importance, and news of its fall caused great consternation in Athens. It was blamed on Thucydides, although he claimed that it was not his fault and that he had simply been unable to reach it in time. Because of his failure to save Amphipolis, he was sent into exile:

| “ | It was also my fate to be an exile from my country for twenty years after my command at Amphipolis; and being present with both parties, and more especially with the Peloponnesians by reason of my exile, I had leisure to observe affairs somewhat particularly. | ” |

Using his status as an exile from Athens to travel freely among the Peloponnesian allies, he was able to view the war from the perspective of both sides. During this time, he conducted important research for his history.

This is all that Thucydides tells us about his own life, but we are able to infer a few other facts from reliable contemporary sources. Herodotus tells us that Thucydides's father's name, Olorus, was connected with Thrace and Thracian royalty. Thucydides was probably connected through family to the Athenian statesman and general Miltiades, and his son Cimon, leaders of the old aristocracy supplanted by the Radical Democrats. Cimon's grandfather's name was Olorus, making the connection exceedingly likely. Another Thucydides lived before the historian and was also linked with Thrace, making a family connection between them very likely as well. Finally, Herodotus confirms the connection of Thucydides's family with the mines at Scapte Hyle.

Education

Although there is no certain evidence to prove it, the rhetorical character of Thucydides's narrative suggests that he was at least familiar with the teachings of the Sophists, traveling lecturers who frequented Athens and other Greek cities.

It has also been asserted that Thucydides's strict focus on cause and effect, his fastidious devotion to observable phenomena to the exclusion of other factors and his austere prose were influenced by the methods and thinking of early medical writers such as Hippocrates of Kos. Some have gone so far as to assert that Thucydides had medical training.

Both of these theories are inferences from the perceived character of Thucydides's history. While neither can be categorically rejected, there is no firm evidence for either.

Character

Inferences about Thucydides's character can only be drawn (with due caution) from his book. His sardonic sense of humor is evident throughout, as when, during his description of the Athenian plague, he remarks that old Athenians seemed to remember a rhyme which said that with the Dorian War would come a "great death". Some claimed that the rhyme was actually about a "great dearth" (limos), and was only remembered as "death" (loimos) due to the current plague. Thucydides then remarks that, should another Dorian War come, this time attended with a great dearth, the rhyme will be remembered as "dearth," and any mention of "death" forgotten.

Thucydides admired Pericles, approving of his power over the people, and shows a palpable distaste for the pandering demagogues who followed him. Thucydides did not approve of the democratic mob nor the radical democracy that Pericles ushered in but felt that it was acceptable in the hands of a good leader. Generally, Thucydides exhibits a lack of bias in his presentation of events, refusing, for example, to minimize the negative effect of his own failure at Amphipolis. Occasionally, however, strong passions break through, as in his scathing appraisals of the demagogues Cleon and Hyperbolus. Cleon has sometimes been connected with Thucydides's exile, which would suggest some bias in his presentation of him, but it should be noted that this connection is first made in a (not entirely reliable) biography written centuries after Thucydides's death, and may equally be no more than a backwards inference from Thucydides's evident disapproval of Cleon.

Thucydides was clearly moved by the suffering inherent in war and concerned about the excesses to which human nature is apt to resort in such circumstances. This is evident in his analysis of the atrocities committed during civil conflict on Corcyra, which includes the memorable phrase "War is a violent teacher".

The History of the Peloponnesian War

Thucydides wrote only one book: its modern title is the History of the Peloponnesian War. His entire contribution to history and historiography is contained in this one dense history of the 27-year war between Athens and its allies, and Sparta and its allies. The history breaks off near the end of the 21st year. Thucydides wanted to create an epic that would depict an event of greater importance than any previous war that the Greeks had fought.

Thucydides is generally regarded as one of the first true historians. Like his predecessor Herodotus (often called "the father of history"), Thucydides places a high value on autopsy and eye-witness testimony, and writes about many episodes in which he himself probably took part. He also assiduously consulted written documents and interviewed participants in the events that he records. Unlike Herodotus, he did not recognize divine interventions in human affairs. He may have held unconscious biases—to modern eyes, he seems to underestimate the importance of Persian intervention—but he was the first historian who attempted anything like modern historical objectivity.

One major difference between Thucydides's history and modern historical writing is that the former includes lengthy speeches that, as he himself states, were as best as could be remembered of what was said—or, perhaps, what he thought ought to have been said. These speeches are composed in a literary manner. Pericles' funeral oration, which includes an impassioned moral defence of democracy, heaps honour on the dead:

| “ | The whole earth is the sepulchre of famous men; they are honoured not only by columns and inscriptions in their own land, but in foreign nations on memorials graven not on stone but in the hearts and minds of men. | ” |

Although attributed to Pericles, this passage appears to have been written by Thucydides for deliberate contrast with the account of the plague in Athens which immediately follows it:

| “ | Though many lay unburied, birds and beasts would not touch them, or died after tasting them [...]. The bodies of dying men lay one upon another, and half-dead creatures reeled about the streets and gathered round all the fountains in their longing for water. The sacred places also in which they had quartered themselves were full of corpses of persons who had died there, just as they were; for, as the disaster passed all bounds, men, not knowing what was to become of them, became equally contemptuous of the gods' property and the gods' dues. All the burial rites before in use were entirely upset, and they buried the bodies as best they could. Many from want of the proper appliances, through so many of their friends having died already, had recourse to the most shameless sepultures: sometimes getting the start of those who had raised a pile, they threw their own dead body upon the stranger's pyre and ignited it; sometimes they tossed the corpse which they were carrying on the top of another that was burning, and so went off. | ” |

Classical scholar Jacqueline de Romilly first pointed out, just after the second world war, that one of Thucydides's central themes was the ethic of Athenian imperialism. Her analysis put his history in the context of Greek thought on the topic of international politics. Since her fundamental study, many scholars have begun studying the theme of power politics, id est realpolitik, in Thucydides's history.

On the other hand, some authors, including Richard Ned Lebow, reject the common perception of Thucydides as a historian of naked realpolitik. They argue that actors on the world stage who had read his work would all have been put on notice that someone would be scrutinising their actions with a reporter's dispassion, rather than the mythmaker's and poet's compassion and were thus consciously or unconsciously participating in the writing of it. Thucydides's Melian dialogue is a lesson to reporters and to those who believe that one's leaders are always acting with perfect integrity on the world stage. It can also be interpreted as evidence of the moral decay of Athens from the shining city on the hill Pericles described in the Funeral Oration to a power-mad tyrant over other cities.

Thucydides does not take the time to discuss the arts, literature or society in which the book is set and in which he himself grew up. He was writing about an event, not a period, and as such took lengths not to discuss anything unrelated.

Leo Strauss, in his classic study The City and Man—see especially pp. 230–31—argued that Thucydides had a deeply ambivalent understanding of Athenian democracy: on one hand, "his wisdom was made possible" by the Periclean democracy, on account of its liberation of individual daring and enterprise and questioning; but this same liberation spurred the immoderation of limitless political ambition and thus imperialism, and eventually civic strife. This is the essence of the tragedy of Athens or of democracy — this is the tragic wisdom that Thucydides conveys, which he learned in a sense from Athenian democracy. More conventional scholars view him as recognising and teaching the lesson that democracies do need leadership—and that leadership can be dangerous to democracy.

Thucydides versus Herodotus

Thucydides and his immediate predecessor Herodotus both exerted a significant influence on Western historiography. Thucydides does not mention his counterpart by name, but his famous introductory statement

| “ | To hear this history rehearsed, for that there be inserted in it no fables, shall be perhaps not delightful. But he that desires to look into the truth of things done, and which (according to the condition of humanity) may be done again, or at least their like, shall find enough herein to make him think it profitable. And it is compiled rather for an everlasting possession than to be rehearsed for a prize. | ” |

is thought to refer to him.

Herodotus records in his Histories not only the events of the Persian Wars but also geographical and ethnographical information, as well as the miraculous and mythical stories ("fables") related to him during his extensive travels. If confronted with conflicting or unlikely accounts, he leaves the reader to decide what to believe. The work of Herodotus is reported to have been read ("rehearsed") at festivals, where prizes were awarded, as at Olympia.

Herodotus views history as a source of moral lessons, with conflicts and wars flowing from initial acts of injustice that propagate through cycles of revenge. In contrast, Thucydides claims to confine himself to factual reports of contemporary political and military events, based on unambiguous, first-hand, eye-witness accounts, although - unlike Herodotus - he does not reveal his sources. Thucydides views life exclusively as political life, and history in terms of political history. Morality plays no role in the analysis of political events while geographic and ethnographic aspects are, at best, of secondary importance.

Thucydides was held up as a paragon of truthful history-writing by subsequent Greek historians like Ctesias, Diodorus, Strabo, Polybius and Plutarch. Lucian refers to Thucydides as having given Greek historians their law, requiring them to say what had been done (ὡς ἐπράχθη). Greek historians of the 4th century BC accepted that history was political history and that contemporary history was the proper domain of a historian. Unlike Thucydides, however, they continued to view history as a source of moral lessons. Some of them wrote pamphlets denigrating Herodotus, the "father of lies", although the Roman politician and writer Cicero dubs him the "father of history."

Thucydides and Herodotus were largely forgotten during the Middle Ages, but the latter became highly respected again in the 16th and 17th century, in part due to the discovery of America, where customs and animals were encountered even more surprising than those related by Herodotus, and in part because of the Reformation, during which the Histories provided a basis for establishing biblical chronology as advocated by Isaac Newton.

Even during the Renaissance, Thucydides attracted less interest among historians than his successor Polybius. Although Niccolò Machiavelli, the 16th century Florentine political philosopher who wrote Il Principe (The Prince), in which he held that the sole aim of a prince (politician) was to seek power regardless of religious or ethical considerations, does not much mention Thucydides, later authors have observed a close affinity between them. In the 17th century, the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, the author of an influential book, Leviathan, which advocated highly authoritarian systems of government, was an admirer of Thucydides and wrote an important translation in 1628. Thucydides, Hobbes and Machiavelli are together considered the founding fathers of political realism, according to which states are primarily motivated by the desire for military and economic power or security, rather than ideals or ethics.

The reputation of Thucydides was greatly revived in the 19th century. A cult developed among German philosophers like Friedrich Schelling, Friedrich Schlegel and Friedrich Nietzsche, who claimed that, "in him [Thucydides], the portrayer of man, that culture of the most impartial knowledge of the world finds its last glorious flower." Among leading historians, such as Eduard Meyer, Macaulay, and Leopold von Ranke, who developed modern source-based history writing, Thucydides was again the model historian. They valued in particular the philosophical and artistic component of his work. However, the reputation of Herodotus was high as well among German historians: the history of civilization was increasingly viewed as complementary to political history.

In the 20th century, a different mode of historiography was pioneered by Johan Huizinga, Marc Bloch and Braudel. This was not inspired by Thucydides; instead, it emphasized the study of long-term cultural and economic developments, and the patterns of everyday life, over that of political history. The Annales School, which represents this direction, has been viewed as extending the tradition of Herodotus. At the same time, the influence of Thucydides became increasingly prominent in the area of international relations through the work of Hans Morgenthau, Leo Strauss and Edward Carr.

The tension between the Thucydidean and Herodotean traditions extends beyond historical research. According to Irving Kristol, considered the founder of American Neoconservatism, Thucydides wrote "the favorite neoconservative text on foreign affairs," and Thucydides is a required text at the Naval War College. On the other hand, author and labour lawyer Thomas Geoghegan recommends Herodotus as a better source than Thucydides for drawing historical lessons relevant for the present.

Thucydides in popular culture

In 1991, the BBC broadcast a new version of John Barton's 'The War that Never Ends', which had first been performed on stage in the 1960s. This adapts Thucydides' text, together with short sections from Plato's dialogues. More information about it can be found on the Internet Movie Database.

Quotations

- "But, the bravest are surely those who have the clearest vision of what is before them, glory and danger alike, and yet notwithstanding, go out to meet it."

- "The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must."

- "It is a general rule of human nature that people despise those who treat them well, and look up to those who make no concessions."

- "War takes away the easy supply of daily wants, and so proves a rough master, that brings most men's characters to a level with their fortunes."

- "The cause of all these evils was the lust for power arising from greed and ambition; and from these passions proceeded the violence of parties once engaged in contention."

Quotations about Thucydides

- ... the first page of Thucydides is, in my opinion, the commencement of real history. All preceding narrations are so intermixed with fable, that philosophers ought to abandon them, to the embellishments of poets and orators. (David Hume, „Of the Populousness of Ancient Nations“)