Street Children in Kenya

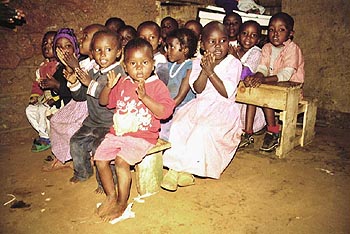

“Street life is dirty, violent and short”, says George Nyakora. As director of SOS Children’s Villages in Kenya, and he should know. In Nairobi, the country’s capital, 250,000 people have no roof over their heads. Of this mass of people ravaged by poverty, war and globalisation, it is the children who have to struggle most. Some are sent out by their impoverished parents to work or to beg. Others have lost their families through war or illness, and some have simply been abandoned because they have become too much of a burden. These street children scrabble to maintain the most basic form of existence. They polish shoes, wash windscreens, pick pockets and beg. Most of them take drugs when they can, are malnourished and are sick.

“Street life is dirty, violent and short”, says George Nyakora. As director of SOS Children’s Villages in Kenya, and he should know. In Nairobi, the country’s capital, 250,000 people have no roof over their heads. Of this mass of people ravaged by poverty, war and globalisation, it is the children who have to struggle most. Some are sent out by their impoverished parents to work or to beg. Others have lost their families through war or illness, and some have simply been abandoned because they have become too much of a burden. These street children scrabble to maintain the most basic form of existence. They polish shoes, wash windscreens, pick pockets and beg. Most of them take drugs when they can, are malnourished and are sick.

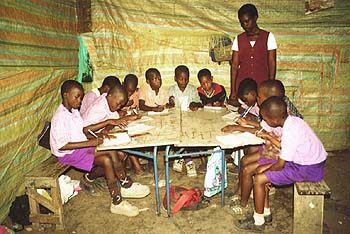

SOS Children’s Villages established its project in Nairobi as long ago as 1973. Since then the work to help the town’s street children has expanded considerably. Recently a programme called “Give a Child a Good Start” was launched in partnership with Unilever. Its aim is to feed the homeless, and recently a “street breakfast” was organised which was attended by over 400 children. This successful SOS Unilever partnership has developed further to help with the refurbishment of a children’s hostel in Ngara, one of the Nairobi’s poorest districts.

The rescue and rehabilitation of street children is not easy. The very nature of their desperate existence has played a significant role in shaping their characters. They tend to be strongly independent. They wouldn’t survive on the streets if they weren’t. Re-socialising these young people can be a tough task. Attempts to lead them too rapidly into a new environment which involves social constraints and different patterns of behaviour can lead to failure. They find a return to the streets more attractive than a difficult integration into a society that is foreign to them.

A tolerant step by step approach is essential. And gradually, as the children are relieved of the day to day pressures of managing their own survival, they become increasingly keen to learn and take part in social activities.

“These young people have potential”, says George Nyakora, “all they need is someone who will listen to them, and a little help.

Return to Schools Wikipedia Home page…

Return to Schools Wikipedia Home page…